Main Body

Module 5 How Accurate are Gender Differences in Physical, Cognitive, and Emotional Abilities?

Case Study: Harvard’s President Sparked a Gender Controversy

In January 2005, the president of Harvard University, Lawrence H. Summers, sparked an uproar during a presentation at an economic conference on women and minorities in the science and engineering workforce (Goldin et al., 2005). During his talk, Summers proposed three reasons why there are so few women who have careers in math, physics, chemistry, and biology. One explanation was that it might be due to discrimination against women in these fields, and a second was that it might be a result of women‘s preference for raising families rather than for competing in academia. In addition, Summers also argued that women might be less genetically capable of performing science and mathematics, and that they may have less intrinsic aptitude than men.

Summers‘s comments on genetics set off a flurry of responses. One of the conference participants, a biologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, walked out on the talk, and other participants said that they were deeply offended. Summers replied that he was only putting forward hypotheses based on the scholarly work assembled for the conference, and that research has shown that genetics have been found to be very important in many domains, compared with environmental factors. As an example, he mentioned the psychological disorder of autism, which was once believed to be a result of parenting but is now known to be primarily genetic in origin.

The controversy did not stop with the conference. Many Harvard faculty members were appalled that a prominent person could even consider the possibility that mathematical skills were determined by genetics and the controversy and protests that followed the speech led to the first ever faculty vote for a motion expressing a “lack of confidence” in a Harvard president. Summers resigned his position in 2006, in large part as a result of the controversy.

Lawrence Summers‘s claim about the reasons why women might be underrepresented in the hard sciences was based in part on the assumption that environment, such as the presence of gender discrimination or social norms, was important but also in part on the possibility that women may be less genetically capable of performing some tasks than are men. Is this true?

In this module, we will discuss the content of gender stereotypes. We will then consider what the research has to say about the accuracy of these beliefs.

Content of Gender Stereotypes

A stereotype is a shared belief about a social group. Gender stereotypes are shared beliefs about the traits, abilities, and characteristics associated with men and women. Noticed that in the definition of stereotypes it states that these are shared beliefs, not personal beliefs. Psychologists do not consider personally held beliefs to be stereotypes unless they are shared by many other people in your culture.

In the last several decades more women have entered the labor force. In 1950 about one in three women were in the workforce, which jumped to almost six out every ten women in 2018, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018). Women now earn more college degrees at every degree level (Bachelor’s Master’s and Doctoral) than do men (Okahana & Zhou, 2018). Have the cultural stereotypes changed to reflect these changes in the lives of women and men?

Most of the research on the content of gender stereotypes has highlighted two themes: agency and communion. Agency includes characteristics such as assertiveness and effectiveness, traits that facilitate leadership and success. Communion includes characteristics such as kindness and warmth, traits that facilitate connection with and concern for others. It is important to note that communion and agency are not polar opposites; they are separate dimensions that social groups fall along. Fiske et al. (2002) found that the elderly are viewed as more “warm”, a trait of communion, while they are viewed as less competent, a trait found in agency. Those who are wealthy are viewed as less warm, but more competent; as are men. Those who are poor are viewed as low on both traits. While women are viewed as moderately competent, but high in warmth. These beliefs about social groups influence our expectations and behaviors when we interact with people. Moreover, these two dimension underlie many of our gender stereotypes. In the US culture, and many other Western cultures, “masculine” traits often reflect agency, while many of the “feminine” traits reflect communion. Even the social roles and occupations typical of men and women highlight these two dimensions.

| Male Stereotype: Social Role | Female Stereotype: Social Role |

| Financial provider | Tends to the home |

| Leader | Provides emotional support |

| Makes major decisions in the home | Takes care of children |

| Male Stereotype: Occupations | Female Stereotype: Occupations |

| Construction worker | Secretary |

| Firefighter | Nurse |

| Politician | School teacher |

Have Gender Stereotypes Changed?

As mentioned above, women have entered the labor force and levels of professional education in greater numbers. Have the gender stereotypes changed at all to reflect the reality of our society? In 2016, Haines et al. compared social perceptions of men and women in 2014 to data from the 1980s. The researchers compared people’s perceptions on eight components: agency traits, communal traits, male gender role, female gender role, male-typed occupations, female-typed occupations, male-typed physical characteristics, and female-typed physical characteristics. Their findings suggest that even in 2014 people still saw large differences between men and women that are consistent with the traditional gender stereotypes. For all eight components the differences in how people viewed men and women were statistically significant and the effect sizes were medium to large on all but agency. Moreover, the 2014 data looked remarkably similar to the data from 1983. The researchers also found that the participants’ sex had little impact on how they viewed men and women. However, men were more likely to view females as having more feminine physical traits than were women.

| Components Assessed | Effect Size (d value) |

|---|---|

| Agency Traits | +.27 (small) |

| Communal Traits | -.57 (medium) |

| Male gender role | +.56 (medium) |

| Female gender role | -.75 (large) |

| Male-typed occupations | +.58 (medium) |

| Female-typed occupations | -.55 (medium) |

| Male-typed physical characteristics | +.63 (medium) |

| Female-typed physical characteristics | -.60 (medium) |

| + effect sizes denote males rated more likely, – effect sizes denote females rated more likely | |

In an effort to have a more culturally representative sample, Eagly et al. (2020) compared opinion polls from large national surveys across 7 decades, from 1946 to 2018. Their research suggests some stability, but also that there have been some changes in people’s perceptions of men and women over time. Questions in these surveys that assessed perceptions of communion showed that women were, and still are, viewed as possessing more of these traits. In fact, more people today ascribe these traits to women than in the past. In 1946, 54% of respondents who saw a gender difference in these traits said they were truer of women, in 1989, 83% did, and in 2018, 97% did. In addition, fewer people today than in the past see the sexes as equal on communal traits. The survey questions on agency traits suggest that over time there was little change in ascribing these traits to men, however, there has been an increase in the number of people saying the sexes are equal on these traits. However, in a reversal of gender stereotypes among those who saw a gender difference, they were more likely to rate women as being more competent and intelligent in 2018 (65%) than there were in 1946 (34%). With the exception of communion and to a lesser extent agency, people are more likely to view men and women as equal in competence and intelligence than to see a sex difference today than in the past.

These studies suggest that there are areas of stability, such as the greater tendency to ascribe agency traits to males and communal traits to females, and that certain occupations and characteristics are still viewed as more typical of men or women along traditional gender stereotypes. While at the same time there has been some change. More people see men and women as being equal than was the case in the past.

Is the Content of Gender Stereotypes Universal?

Most of the research on gender stereotypes has been conducted in the US (Bossen, et al., 2019). What about other cultures? There is some evidence to suggest that many cultures hold similar views about the content of gender stereotypes. Women are often seen as affectionate and more agreeable, while men are viewed as being more dominant and adventurous (Cuddy, et. al., 2009). These similarities reflect the agency and communion distinction. However, there are some notable differences in how cultures view the genders. Nations differ in certain core cultural values. Some nations are described as being collectivistic cultures, such as many African, East Asian, and Middle Eastern nations, who value the needs of the group over individuals. As a result, such cultures would value more communal traits. In contrast, other nations are described as individualistic cultures, such as the United States, Canada, and many Western European countries, who emphasize the individual rather than the group. These nations are more likely to value agentic traits. Cuddy et. al. (2015) analyzed the responses to 21 traits that clearly captured individualism, and 27 traits that captured collectivism and they found an interesting pattern. The researchers predicted that the more dominant group (men) would be seen as holding more of the traits valued in that society. In collectivistic cultures people were more likely to associate collectivistic traits to men, while in individualistic cultures more individualistic traits were assigned to men. While this seems to challenge research showing considerable similarity across cultures in the content of gender stereotypes, it does reveal a universal tendency. Whatever traits are valued by a culture they are more likely to be ascribed to men than to women.

Physical Abilities

Activity Level:

A common stereotype is that males, especially younger males, are much more active than females. Research does indeed support the finding that males exhibit a higher activity level than females (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). However, age is a determining factor when measuring just how much more active males are, as the smallest difference occurred between infants and the largest difference for those oldest. What accounts for the gender differences? Else-Quest and Hyde provide two hypotheses. First, they propose that the gender segregation effect, which states that children seek out and play with other children of the same gender, results in boys encouraging other boys to be more and more active. The second hypothesis focuses on the advanced physical development of girls, especially in brain development, that allows girls a greater ability to control their activity level due to their greater maturity. Gender differences associated with specific ages are presented in the following table:

| Age of Participants | Effect size (d value) |

| Infants | .29 (small) |

| Preschoolers | .44 (medium) |

| Older Children and Adults | .64 (medium) |

| All Ages | .50 (medium) |

Strength, Endurance, and Movement:

Courtright et al. (2013) analyzed data from 113 studies using 140 unique samples assessing the physical abilities of men and women. They found substantial differences between the genders on many of the measures. Overall, men showed more muscle strength, although it varied by body area, muscle tension (exerting force against an object), muscle power (exerting force quickly), and muscular and cardio endurance. Movement quality, including flexibility, coordination, and balance showed slight to moderate gender differences, with some measures favoring women and others favoring men. Others, like Hyde (2005) or Hines (2015) show a slight female advantage for balance, which challenge the findings of Courtright et al. on this measure.

| Physical Ability Measure | Effect Size (d value) |

|---|---|

| Muscle strength (Upper) | 1.88 (very large) |

| Muscle strength (Lower) | 1.60 (very large) |

| Muscle strength (Core) | .25 (small) |

| Muscle strength (Total body) | 2.22 (very large) |

| Muscle tension | 2.13 (very large) |

| Muscle power | 1.11 (very large) |

| Muscle endurance | 1.47 (very large) |

| Cardio endurance | 1.81 (very large) |

| Movement quality (Flexibility) | -.15 (small) |

| Movement quality (Coordination) | .64 (medium) |

| Movement quality (Balance) | .31 (small) |

| Source: Courtright et al., 2013. | |

Who is better at running a marathon, women or men? As Hubble and Zhao (2016) suggest, the answer depends on how you define “better”. Men are faster, even at ultra-long distance they often finish the race first. While women have better strategy and pacing throughout the race. They show less variation in their speeds, while men tend to slow down as the race progresses. It may be that the success of men in their race times is due to their faster initial speed. Hubble and Zhao note that some researchers have suggested that the female body’s ability to store and metabolize fat more efficiently than the male body may allow women to keep a steady pace throughout the race. However, others have suggested that men’s overconfidence may also be a factor in their less efficient race strategy. In most ultra-endurance events men are faster, whether it be cycling, running, or triathlon (Knechtle et al., 2015). However, the story is different when it comes to open water ultra-distance swimming. Here women achieve and even surpass the performance of men. In the Catalina Channel Swim, one of the legs of the “Triple Crown of Open Water Swimming” the average race times of the fastest women were faster by almost 53 minutes than the average race times of the fastest male swimmers (Knechtle et al., 2015). Women also hold many records for longest distance or durations in the water. The longest continuous and unaided ocean swim is held by Chloe McCardel, 77.3 miles/124.4 km, and the longest continuous and unaided open water and lake swim is held by Sarah Thomas, 104.6 miles/168.3 km (Marathon Swimmers Federation, 2020).

Throwing:

Throwing requires the coordination of the whole body and is a physical skill used in many team sports and games (Gromeier, et al., 2017). Meta-analyses have revealed gender differences in velocity in children by age three, and in distance by age 2, with males exceeding the abilities of females (Morris et al., 1982; Thomas & French, 1985). Similar results have been shown in adults (van den Tillaar & Ettema, 2004). Are males more accurate at hitting a target than females? Previous research has found that males, both children and adults, show greater accuracy, although many of these studies used novices (Morris et al., 1982; Thomas & French, 1985, Robertson & Konczak, 2001). As males are more likely to have been shown how to throw in childhood this finding is not surprising. Gromeier and colleagues (2017) assessed throwing in children age 6-16 who were all aspiring athletes in sports that involved throwing. They found no difference in the accuracy at all ages. However, they did find gender differences in the developmental pattern of throwing and in the quality of movement that favored males.

Pain:

Clinical settings: Large-scale epidemiological studies often reveal that women report experiencing more pain than do men (Bartley & Fillingim, 2013). Women are more likely than men to report having experienced pain in the last week, and report having more chronic health conditions such as migraine and chronic tension-type headache, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia. In their overview of the pain literature Bartley and Fillingim reported that the trend is towards greater pain in women. However, do women experience more severe pain than men, or are they just more willing to report experiencing pain? It is harder to assess the question of pain severity, as there really is no standard measure of pain perception. Research comparing pain experiences following the same surgical procedures have yielded inconsistent results as to which gender experiences more pain. Part of the problem with such research is that across these studies there were different surgical procedures and pain medications and treatments used.

Experimental settings: Another way to assess pain tolerance and perception is to study men and women under more controlled laboratory conditions. Researchers have used a variety of methods to inflict pain (chemical, electrical, pressure, temperature), and measures of pain (length of time to report pain sensation, how long the participant is willing to experience the pain (tolerance), and self-reports of unpleasantness). The results have suggested than women have more pain sensitivity than do men (Rahim-Williams et al., 2012). In their study of healthy young men and women, women reported more pain and less pain tolerance, although the effect sizes were from small to large depending on the method and type of measure. The mechanisms behind the gender differences in pain in both clinical and experimental settings are not clear. It has been suggested that both biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors may contribute (Bartley & Fillingim, 2013).

| Measure of Pain | Effect Size (d value) |

|---|---|

| Heat pain | .48 (medium) |

| Heat pain tolerance | .98 (large) |

| Cold pain | .41 (medium) |

| Cold pain tolerance | .55 (medium) |

| Pressure pain (trapezius muscle) | .90 (large) |

| Pressure pain (masseter muscle) | .98 (large) |

| Ischemic pain (lack of circulation) | .24 (small) |

| Ischemic pain tolerance | .52 (medium) |

| Source: Rahim-Williams et al., 2012 | |

Differences in the relative levels of sex hormones has been touted as one possible source for the gender differences in pain. Estrogen and progesterone have a complex effect on pain, in that they can both enhance or inhibit pain perception (Smith et al., 2006). This may explain why the research findings are often mixed on how this relates to women’s experience of pain depending on the levels of these two hormones, with some research suggesting that women show greater sensitivity to pain depending on the phase of the menstrual cycle (Riley et al., 1999), and others not finding any consistent pattern between menstrual cycle hormone levels and pain perception (Bartley & Rhudy, 2013). In contrast, studies have shown that testosterone appears to be more protective from pain sensitivity (Cairns & Gazerani, 2009).

Comparing the coping styles used by men and women reveals that women catastrophize more than men (Forsythe et al., 2011). Catastrophizing refers to assuming the worst case scenario when faced with a challenge, and research has tied this tendency with greater pain sensitivity, lower pain tolerance, and greater pain-related disability (Keefe et al., 1989). In addition, self-efficacy, the belief that you can achieve certain outcomes, has been studied with regard to ability to cope with pain. Those with lower self-efficacy report more pain and other physical symptoms (Somers et al., 2012). Finally cultural expectations about masculinity and femininity may also play a role. Expression of pain is typically more acceptable for women, which may lead more women to report that they are in pain (Bartley & Fillingim, 2013).

Brain Areas: Relative Size and Functioning

Looking at overall brain volume, the male brain is slightly larger as brain size correlates with body size (Hines, 2011). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create images of the body, have identified some gender differences in brain size and performance. Although males and females perform equally on tests of intelligence, females with higher IQ scores show more gray matter (neuronal cell bodies) and white matter (myelinated axons) in frontal brain areas associated with language. For males, higher IQ scores correlate with more gray matter in posterior areas that integrate sensory information (Haier, 2009). However, when comparing males and females directly on tasks, anatomical and functional differences typically do not result in differences in performance (Hines, 2011). It may be that these differences allow male and female brains to behave the same way despite being physiologically different.

Looking at cortical size differences in specific brain areas, MRI research has identified some variations between male and female brains (Cahill, 2012). However, size differences in specific brain areas are relative to the overall brain size, and there are certainly individual differences. In males, the amygdala, which responds to emotional arousal, and sections of the parietal cortex, involved in spatial perception, are usually larger.

In females, parts of the frontal cortex, responsible for higher-level cognitive skills, and limbic cortex, involved in emotional processing, are typically larger. Additionally, females exhibit a greater density of neurons in the temporal lobe, which is associated with language comprehension and processing. This greater density correlates with tests that demonstrate a verbal fluency advantage for females. Lastly, females tend to possess a larger hippocampus, which is responsible for memory processing and storage. Reviewing the research on male and female navigation, this difference support the theory that the larger hippocampus for females may be why they navigate using landmarks. In contrast, males tend to navigate by “dead reckoning” or estimating distances using space and orientation cues (Cahill, 2012).

What causes these anatomical differences? Research has identified the importance of sex hormones released during the prenatal period. Researchers theorize that the hormones “help direct the organization and wiring of the brain during development and influence the structure and neuronal density of various regions,” (Cahill, 2012, p. 25). Consequently, these brain differences appear to have been present since birth rather than acquired due to socialization or hormonal changes at puberty. However, other differences may be due to numerous environmental influences that affect the size and functioning of specific brain areas. Even with these differences, male and female brains function similarly for most tasks (Hines, 2011).

Are there gender differences during sexual activity? During sexual arousal, the ventromedial area of hypothalamus is activated in women, while the medial pre-optic region of hypothalamus is activated during men’s sexual responses (Petersen & Hyde, 2011). Additionally, the hypothalamus and the amygdala are activated more in men than women. Lastly, the cingulate gyrus, important in processing emotions and regulating behaviors, and thalamus, the relay station for sensory information, are also activated more in men.

Cognitive Abilities

Cognition is thinking, and it encompasses the processes associated with perception, knowledge, problem solving, judgment, language, and memory (Lally & Valentine-French, 2018). Given the variety of tasks included in these processes, it is not surprising that gender differences have been researched. According to Hyde (2005), most results reflect the gender similarities hypothesis, which states that females and males are similar on most, but not all, psychological variables. After reviewing 46 meta-analyses of gender-based research, Hyde found that 78% of the gender differences noted were small or very close to zero. Below we will consider performance on intelligence, mathematical, spatial, and verbal abilities to determine if gender differences are evident. Explanations for those gender differences are also examined.

Intelligence:

Intelligence is the ability to think, learn from experience, solve problems, and adapt to new situations (Lally & Valentine-French, 2018). The study of gender differences in intelligence has a lengthy and checkered past. In the 1800s women were viewed as intellectually inferior to men and some early researchers attempted to use the new science of psychology to justify women’s lower social status (Bosson et al., 2019). However, men and women have almost identical intelligence as measured by standard IQ and aptitude tests (Hyde, 2005). Despite this, there is variability in intelligence, in that more men than women have very high, as well as very low, intelligence, known as the greater male variability hypothesis (Gray et al. 2019). There are also observed gender differences on some types of tasks. Women tend to do better than men on some verbal tasks, including spelling, writing, and pronouncing words (Halpern et al., 2007; Nisbett et al., 2012), and they have better emotional intelligence in the sense that they are better at detecting and recognizing the emotions of others (McClure, 2000).

Mathematical Performance:

Computations and the understanding of math concepts for grades 2 through 11 show no significant gender differences. Complex mathematical problem solving in high school do show a slight advantage for males in some, but not all, national assessments, and this difference is lower than in previous analyses, according to Hines (2015). Advanced tests, such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and Graduate Record Exam (GRE) do show differences that favor males on the math portions of the tests (Hines, 2015). These differences may be inflated because of self-selection, in that more males than females drop out of education. Consequently, a smaller number of lower achieving males actually take these tests. It also must be noted that gender differences in math self-confidence (higher in males) and math anxiety (higher in females) are actually larger than any gender difference in actual math performance (Hyde, 2014). In addition, cross-cultural research does not always show a male advantage in math, and nations with greater gender equality show less of a gap in math performance (Reilly, 2012).

Computations and the understanding of math concepts for grades 2 through 11 show no significant gender differences. Complex mathematical problem solving in high school do show a slight advantage for males in some, but not all, national assessments, and this difference is lower than in previous analyses, according to Hines (2015). Advanced tests, such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and Graduate Record Exam (GRE) do show differences that favor males on the math portions of the tests (Hines, 2015). These differences may be inflated because of self-selection, in that more males than females drop out of education. Consequently, a smaller number of lower achieving males actually take these tests. It also must be noted that gender differences in math self-confidence (higher in males) and math anxiety (higher in females) are actually larger than any gender difference in actual math performance (Hyde, 2014). In addition, cross-cultural research does not always show a male advantage in math, and nations with greater gender equality show less of a gap in math performance (Reilly, 2012).

Spatial Performance:

There are several measures of spatial ability, and gender differences vary based on the aspect being assessed. Mental rotation refers to the ability to rotate an object in one’s mind and is a frequent way to measure spatial skills by assessing a person’s ability to mentally rotate a three-dimensional object to match a target. Males have consistently demonstrated stronger skills on mental rotation tasks, and this gender difference is one of the largest in cognitive skills, with effect sizes often ranging from .47 to .73 (Lauer et al., 2019). However, this gap may be due to a lack of training provided by out-of-school experiences that favor males, such as playing video games. Researchers have also found that the male advantage in mental rotation in middle-school predicted gender differences in science achievement (Geer et al., 2019). Spatial perception refers to the ability to perceive and understand space relations between objects. An example would be the ability to identify the true horizontal water level in a tilted container. Males show a small advantage in childhood (d=.33) which increases in adulthood (d=.48; Voyer et al., 1995). Spatial visualization, which refers to complex, sequential manipulations of spatial information including embedded figures, shows only a small to negligible difference between genders (d<.20; Hines, 2015). Spatial location memory, which is the ability to remember the location of objects in physical space, shows a slight female advantage (d=-.27; Voyer et al., 2007). This difference has often been attributed to women’s historical division of labor as gatherers, but not all researchers agree with this explanation.

Verbal Skills:

In children, girls acquire language earlier than boys and demonstrate a larger vocabulary between the ages of 18 to 60 months (Hines, 2015). Reilly et al. (2018) analyzed 27 years of data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress on reading and writing skills. This analysis involved 3.9 million United States students in the fourth, eighth, and twelfth grades. Results indicated that girls, on average, scored significantly higher than boys in both reading and writing at the fourth grade. This gap increased further at the eighth grade level and then even further at the twelfth grade. At all three grade levels, differences were greater for writing than reading skills. Additionally, a review of international data consisting of 65 nations indicated that female 15-year-olds scored higher in reading comprehension (Hyde, 2014). Females also show a small to moderate (-.24 to -.45; Weiss et al., 2003) advantage on measures of verbal fluency, the ability to generate words. Overall, verbal skills appear to be an exception to the Gender Similarities Hypothesis.

Non-Verbal Communication:

Females smile more and the effect size is medium (d=-.41; LaFrance et al., 2003) and this holds across cultures and ethnicities (Tsai et al., 2016). LaFrance et al. (2003) found that this may be due to women being more likely to occupy nurturing and caring roles, as both sexes smiled more when parents, therapists or medical professionals. Women make more eye contact than do men when interacting with others, with the highest eye contact occurring between female dyads (LaFrance & Vial, 2016). Although males tend to look more at females when speaking to them, and look away when women are talking to them, while women do the reverse, they are more likely to look at their partner when listening than when speaking (Bosson et al., 2019).

Explanations for Gender Differences in Cognitive Abilities

Why might we find gender differences in cognitive abilities? There are likely to be several factors at play. As mentioned previously, when given the opportunity to participate in boys’ activities, such as video games, girls improve on visual spatial tasks. Further, more females with varied academic competencies take advanced achievement tests (e.g., SAT and GRE), while lower achieving males do not. This difference demonstrates a male self-selection bias, especially in mathematics. When reviewing cultural differences, gender differences are not consistent across countries. In nations with greater gender equality, gender differences are nonexistent or favor females. Specifically, the female advantage in writing correlates positively with gender equality, while the male advantage in mathematics correlates negatively with gender equality (Hines, 2015). Lastly, males do show greater variation in intelligence, perhaps because of the greater tendency toward learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, and fragile X syndrome than females (Bosson et al., 2019).

Gender stereotypes also play a role in performance. For instance, the poorer math performance by females on high stakes tests, such as the SAT, despite often having equivalent math grades in high school with males, may reflect females’ lack of confidence rather than actual ability. Could this lack of confidence be due to the cultural stereotypes about females and math? Stereotype threat refers to the anxiety that people feel when they risk confirming the cultural stereotype for their group. When females are reminded of the negative stereotypes associated between their gender group and math their performance drops (Keller, 2002). Smeding and colleagues (2013) found that even the order of administration of math and verbal tests can affect the test scores of females. Placing the math test first reduced performance on the math test for females, but females’ performance on the math test was as good as the males’ performance when the verbal test came first. The order of the tests did not affect females’ performance on the verbal test, nor males’ math or verbal scores. Meta-analyses reveal that stereotype threat on women’s math performance ranges from small to moderate (Picho et al., 2013).

How willing are you to guess when you do not know the answer on an important test? When there is no penalty for guessing, research shows that everyone attempts the questions, but when there is a penalty, males are more likely to take the risk (Baldiga, 2013). Overall, guessing may be the better strategy. People tend to do better on a test when guessing the answer than when leaving the question blank and as a result of men’s willingness to take risks they may score slightly higher on some high stakes tests. This may explain an interesting paradox. In general, females get better grades in high school and college, but score slightly lower on tests like the SAT than males (Bosson et al., 2019). Females’ unwillingness to take a chance might explain this discrepancy.

Is there a gender difference in achievement motivation? Achievement motivation refers to an individual’s needs to meet goals and accomplish things. Some scholars have thought that the male advantage in spatial skills and math might reflect less motivation by females to continue to complete work when faced by failure. Yet the research does not support this. In school, females show greater intrinsic motivation to succeed than do males; it is males who are more likely to avoid completing work in the face of failure (Spinath et al., 2014).

Of all things that people can fear, success is not usually at the top of people’s lists. However, fear of success has been studied since the 1960s when Horner (1969) initially described it as women’s motivation to avoid being too successful for fear of social rejection. In Horner’s classic study women were presented with a story about Anne, and men were presented with a story about John, both were described as being at the top of their class in medical school. Participants were asked to complete the story about the character they had been given. Men wrote about how John was happy and satisfied with his success, while 65% of women’s stories reflected concerns that Anne might be rejected by others or even denied the reality of her being successful. Given the time period, the results are not really that surprising. Despite the women’s movement, many women were still limited in their career choices. Their concerns often reflected the reality Anne might face.

Later research expanded fear of success to include the anxiety that women and men might feel when achieving success in an atypical gender situation (Cherry & Deaux, 1978). In their study participants read about Anne and John being at the top of either their nursing or medical school class. As expected the stories of both men and women contained more concerns and fears when Anne or John were successful in atypical gender careers of that time.

Since this early research, others have expanded the concept beyond academic success. André and Metzler (2011) examined this concept in tennis players. What they found was that fear of success was not so much related to gender, as it was to already being more anxious, having self-doubts, or being preoccupied with rewards. As gender role norms continue to evolve we may see less fear of success being experienced.

Personality Traits

Temperament:

Our temperament is the biologically based emotional and behavioral ways we respond to our environment. Temperament occurs early in life and is correlated with our later personality. For children younger than 13, gender differences are observed in the areas of inhibitory control and attention with females exhibiting higher scores in both areas. In contrast, no differences are noted in the areas of persistence and negative affect (Hyde, 2014).

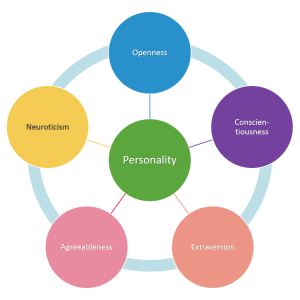

Five Factor Model of Personality:

The Big Five model of personality measures the degree to which an individual demonstrates the following personality attributes: Openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. American data demonstrate that gender differences, when present, are small and tend to get even smaller with age. This is a phenomenon called gender convergence. When difference are found women tend to score slightly higher than men on conscientiousness, agreeableness and neuroticism. Some studies show women may be slightly higher on extraversion, but only on the aspects of extraversion that involve gregariousness, warmth, and positive emotions, while men score higher on the assertiveness and excitement seeking aspects of extraversion (Costa et al., 2001; Weisberg et al., 2011). In contrast, gender differences were not found for Japanese or black South Africans indicating the importance of culture in affecting these gender measurements. Gender stereotypes regarding greater emotionality and tender-mindedness of women are observed in the United States, and they most likely contributed to the gender differences found (Hyde, 2014). Other cultures may not share these stereotypes.

The Big Five model of personality measures the degree to which an individual demonstrates the following personality attributes: Openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. American data demonstrate that gender differences, when present, are small and tend to get even smaller with age. This is a phenomenon called gender convergence. When difference are found women tend to score slightly higher than men on conscientiousness, agreeableness and neuroticism. Some studies show women may be slightly higher on extraversion, but only on the aspects of extraversion that involve gregariousness, warmth, and positive emotions, while men score higher on the assertiveness and excitement seeking aspects of extraversion (Costa et al., 2001; Weisberg et al., 2011). In contrast, gender differences were not found for Japanese or black South Africans indicating the importance of culture in affecting these gender measurements. Gender stereotypes regarding greater emotionality and tender-mindedness of women are observed in the United States, and they most likely contributed to the gender differences found (Hyde, 2014). Other cultures may not share these stereotypes.

Helpfulness:

Who are more helpful, males or females? Gender stereotypes point to females being more caring and nurturing, and consequently they are perceived as more helpful. However, research studies demonstrates the opposite (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). Explanations for males engaging in more helping behavior align with male gender roles of being heroic and chivalrous. Research indicated that males were especially likely to assist in situations that involved danger and when onlookers were present, thus encouraging heroism. Else-Quest and Hyde concluded that the types of behaviors researched favoring males were short-term situations with strangers. In contrast, the frequency of long-term helping behaviors, favoring the nurturing behavior demonstrated by females, are difficult to research.

Emotions

People believe that women are more emotional than are men (Brody & Hall, 2008), but is this true? When we say that women are more emotional do we mean they feel more emotions, they express more emotions, or that they are better at decoding emotions? Men report feeling more pride and anger, while women report feeling more warmth, sadness and anxiety (Brody & Hall, 2010). Given that emotion is highly subjective, self-report measures of emotion are problematic and may reflect gender socialization and stereotypes than true differences (Chaplin et al., 2005).

Emotional Experiences and Expression:

According to Else-Quest and Hyde (2018), the stereotype that females are more emotional than males is among the most pervasive of all stereotypes. Across most cultures, gender stereotypes suggest that females exhibit many more emotions than males, both positive and negative, and most of these emotions reflect powerlessness. In contrast, males are seen as demonstrating fewer emotions, and the ones they do demonstrate reflect dominance. This includes exhibiting more anger, contempt, and pride. However, there are differences among ethnicities indicating that beliefs regarding gendered behavior are socially created rather than biologically based. For example, white women are not supposed to demonstrate anger, but the expressions of anger in other ethnic groups are not seen as a trait only for males.

Research looking at the intensity of emotional expressions found a positive correlation between the level of agreement with gender stereotypes and the intensity of emotional displays for females, but a negative correlation for males (Grossman & Wood, 1993). Specifically, women who held strong gender stereotypes expressed more intense emotions, while men who held strong gender stereotypes exhibited less emotional expression. Does this mean that males do not experience strong emotions? When presented with pictures designed to evoke certain emotions, research does indicate that females are more emotionally expressive than males, but males showed more autonomic nervous system reactivity (MacArthur & Shields, 2015). The authors concluded that males do experience emotions, but societal expectations that they not show them results in males refraining from exhibiting emotional expressions.

Gender differences are also found in how others perceive the emotional expressions exhibited by males and females. Rather than rate women as expressing anger, which goes against gender stereotypes, laboratory experiments demonstrate that participants rate females’ anger expressions as exhibiting sadness instead. Further, when shown pictures of blended emotions, research participants identified males as being angry and females as feeling sad. Not adequately identifying someone’s emotions can interfere with communication patterns and interpersonal relationships. Study participants have also attributed internal versus external factors for reasons why an individual would feel a certain emotion. Participants made more dispositional attributions, or internal reasons, for a female’s expression of emotion, while they assigned more situational attributions, or external reasons, for why a male would exhibit a similar emotion. This would then justify a male’s emotional reaction to a particular situation, whereas for the same response, a female is just being emotional (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, 2009).

In many cultures, women are socialized to be more people/relationship oriented. As a result one would expect females to express more positive emotions that would encourage others to maintain social harmony. Chaplin et al. (2005) state that females are encouraged to exhibit submissive emotions that communicate vulnerability, such as anxiety or sadness, whereas males are encouraged to display disharmonious emotions that convey a highly competitive motivation to achieve and dominate others, such as anger, or gloating when defeating an opponent. Thus, when upset a female may cry while a male may get angry. In their research, Chaplin and colleagues observed how parents responded to their preschool children’s submissive and disharmonious emotions and found that fathers, in particular, were more attentive and supportive of their daughters’ submissive emotions, while ignoring such expressions in their sons. They also were more attentive of son’s disharmonious responses while ignoring such displays in their daughters. These findings would suggest that females are being rewarded when expressing submissive emotions, while boys are rewarded for more disharmonious displays. There is considerable psychological and anthropological research to suggest that emotional expression is culturally constructed (Mesquita et al., 2016).

There is also an assumption that women are better at identifying emotion in others. Male and female participants were equally accurate and quick in identifying anger in the faces of both male and female adults and children, while females were slightly faster at identifying sadness in the faces of females (Parmley & Cunningham, 2014). Wells et al. (2016) also found that women were slightly faster and more accurate at identifying the emotions of other women, than were men in identifying the emotions of either men or women. Overall, research indicates that gender differences in the experience and expression of emotions are exaggerated, and those that are observed often reflect gender roles within the culture rather than an innate difference between males and females.

Empathy:

Who is more empathetic? Empathy refers to our ability to feel what others feel. Empathy involves both understanding how someone might feel in a given context, and feeling those emotions yourself. As many people assume that women are more attuned to the emotions of others, the reasoning goes that women would be more empathetic. However, the answer to the question of who is more empathetic depends on how we measure empathy. On self-reports, women and girls report more empathy for others than do men and boys (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). Self-report research also finds that females who have CAH, thus higher levels of testosterone, report less empathy than other women (Hines, 2015). Experimental research shows women are slightly better than men at determining what someone might be feeling when watching interviews, but this gender difference increases when participants are told that the study is assessing empathy (Bosson et al., 2019). While, brain imaging research reveals no overall gender difference in empathy when observing others who are suffering (Lamm et al., 2011).

Self-Esteem:

Recent research has focused on how adolescent females lose confidence in themselves and experience lower levels of self-esteem, or the positive regard one has for oneself. Media, especially messages regarding attractiveness, and the sexualization of girls that objectify their bodies, negatively affect young female self-perceptions (American Psychological Association, 2007). If self-esteem plummets during adolescence, what happens in adulthood? To assess developmental changes, males and females at various ages rated their overall self-esteem. Results indicated that females do rate themselves lower on self-esteem in early to late adolescence, but then self-esteem rises in adulthood and late adulthood to levels equal to those of males (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). However, looking at gender and ethnicity, while white participants demonstrated a small difference favoring males (+0.20), Blacks demonstrated no difference (-0.04) in self-esteem. These results demonstrate how important intersectionality is when reviewing research results.

| Age of Participants | Effect Size (d value) |

| 7-10 | .16 (small) |

| 11-14 | .23 (small) |

| 15-18 | .33 (small) |

| 23-29 | .10 (close to zero) |

| 60 and Over | .03 (close to zero) |

| All ages | .21 (small) |

Self-Confidence:

While self-esteem measures an overall feeling of self-worth, self-confidence pertains to a belief that one can be successful in a specific area. Not surprisingly, gender differences in self-confidence varied based on the specific area assessed (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). For example, females exhibited higher self-confidence in the areas of behavioral control (d = -.17) and morals/ethics (d = -.38), while males possessed stronger self-confidence in physical appearance (d = .35) and athletics (d =.41). As previously indicated, males rate themselves higher in self-confidence than females in mathematics, and this difference has been interpreted as a female-deficit. However, new perspectives look at this difference as males overestimating their performance and females having a more accurate view of their performance.

Self-Efficacy:

An important area of social cognitive theory is self-efficacy, which refers to one’s belief about being able to accomplish some task or produce a particular outcome (Bandura et al., 2001). Self-efficacy beliefs determine one’s goals and willingness to achieve them. Those with high self-efficacy are more willing to persevere when faced with adversity when others might give-up. Career aspirations are correlated with self-efficacy and often reflect traditional gender roles. When girls observe female nurses, their efficacy for becoming a nurse increases, but when they observe few women doctors, their sense of efficacy for becoming a doctor diminishes.

In the next module we will consider how gender influences sexual behavior. The module starts with describing some of the more common sexual orientation labels, theories on the development of sexual orientation, factors that affect mate selection, and levels of sexual activity.