Main Body

1 Module 10: How does Gender Affect Mental Health?

Mental Health

Girls and women face many challenges and concerns, including interpersonal violence, unrealistic and stereotypical media images, discrimination, oppression, devaluation, limited economic resources, role overload, relationship disruptions, and work inequities, that make them vulnerable to mental health disorders (APA, 2018b). Similarly, traditional masculinity, including stoicism, competitiveness, dominance, and aggression, are associated with less healthy behaviors and more mental health issues in boys and men (APA, 2018a). Further, the extensive stigma and discrimination reported by transgender and gender nonconforming individuals have been correlated with increased rates of depression and suicidality (APA, 2015). The following section will review how gender relates to mental health disorders across the lifespan.

Childhood and Adolescence:

In a review of mental health disorders beginning in childhood and adolescence, Zahn-Waxler et al. (2008) identified gender differences between early-onset and adolescent-onset disorders. Specifically, early-onset disorders are typically exhibited by males, and they include conduct disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, dyslexia, and developmental language disorders. From a biological perspective, prenatal exposure to testosterone has been theorized as a reason as testosterone may slow biological and physical development, including slower maturation of the temporal lobe involved in language. A reduced ability to use language may make it difficult for boys to verbally problem solve during conflicts. Higher fetal testosterone has also been associated with boy’s lower empathy, more restricted interests, and lower quality of social relationships. Infant boys exhibit difficulty regulating and controlling negative emotions, show more anger and irritability, while male preschoolers are more physically active and show less frustration tolerance and impulsivity.

In contrast, adolescent-onset disorders, including depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, are exhibited more by females (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008). Anxiety problems are also more common in girls than boys at an early age. At puberty, estrogen enhances activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which plays an important role in the body’s response to stress. Estrogen appears to delay the ability of females to recover from stress and also results in them becoming more affected than males by long-term stress. Also seen at puberty is greater conformity to the feminine ideal, which is reinforced within cultures. Dependent, emotional, helpless, passive, and self-sacrificing attributes are stereotypically female characteristics, and they are also risk factors for depression.

The more rapid maturation of the brain for girls, especially the frontal cortex, is also thought to increase the tendency to view oneself in comparison to others, and thus result in greater distress internalization (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008). Compared to boys, girls exhibit higher levels of empathy, prosociality, caregiving, guilt and shame, which is due to their greater social awareness. When this increased social awareness is paired with dysfunctional environments, such as marital conflict and parental depression, additional risk for depression occurs. Early maturing girls are especially vulnerable (APA, 2018). Because boys develop later, they are less able to take another’s perspective and less aware of negative family environments. Consequently, this continued egocentricity may protect males from internalizing symptoms, including depression.

Gender dysphoria refers to the strong discomfort or distress caused by a discrepancy between a person’s gender identity and their biological sex assigned at birth, as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Children who actively reject the toys, clothing, and anatomy of their assigned sex and state they prefer the toys, clothing, and anatomy of the opposite sex, may be diagnosed with gender dysphoria in children.

Recent research indicated that 73% of transgender women and 78% of transgender men seeking gender-affirming surgery indicated they first experienced gender dysphoria by age 7 (Zaliznyak, 2020). Childhood gender dysphoria can result in a poor quality of life for the developing child into adolescence. However, some research has indicated that the majority of children with gender dysphoria do not develop gender dysphoria beyond adolescence, and instead these adolescents identify as non-heterosexual (Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2018). Whether gender dysphoria persisted or desisted, typically occurred between the ages of 10 and 13.

Transgender identity persistence in a group of pre-pubertal transgender youth was also analyzed by Steensma et al. (2011, 2013). This research found that 100% of patients who had completely socially transitioned, 60.1% of those who had partially transitioned, and 25.6% of those with who had not socially transitioned reported a transgender identity after 7 years. To further assess persistence, Olsen et al. (2022) followed a cohort of 317 transgender children who completed a social transition prior to age 12. The results indicated that after 5 years of a social transition, 94% of the youth identified as transgender, 2.5% identified as cisgender, and 3.5% identified as nonbinary. The high persistence rates in this study confirmed prior findings and suggested that persistence remains high after starting gender-affirming treatment and socially transitioning.

For adolescents, Santoro (2022) found that transgender and Nonbinary youth experience higher rates of mental health disorders and suicidality. Kaltiala-Heino et al. (2018) reported the results of a school survey indicating that 1.3% of 16–19 year-olds had potentially significant gender dysphoria, and of those adolescents, approximately 40%–45% exhibited clinically significant mental health issues. The most commonly reported conditions were depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicidal ideation/behavior.

Likewise, community-level data indicated that “transgender-identifying youth present four to six times more often with depression and three to four times more often with self-harm and/or suicidal behavior compared with cisgender adolescents” (Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2018, p. 34). Also noted were increased rates of eating disorders and autism spectrum disorders. A lack of parental support was correlated with increased mental health disorders, inadequate housing, and homelessness. In contrast, positive mental health outcomes for transgender adolescents were associated with strong perceived parental support. These outcomes included fewer risk taking sexual behaviors, higher life satisfaction, lower perceived burden of being transgender and fewer depressive symptoms.

Other factors that negatively affect the mental health of transgender youth include a history of being bullied, being afraid for their personal safety, having been hit or harmed, having been in physical fights, having been sexually harassed, and having experienced dating violence (Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2018). Further, transgender youth indicate that school has not been a safe place for them as they have experienced bullying and discrimination by peers and teachers. The negative school environment has resulted in poorer motivation, less ability to concentrate, and school avoidance, all of which has resulted in transgender adolescents dropping-out of school.

Turban et al. (2021) also found that it was not the social transition itself that resulted in mental health concerns for transgender and gender diverse youth. Rather, it was being exposed to an unaccepting school environment. Experiencing bullying and harassment in kindergarten through twelfth grade was correlated with adverse mental health, including increased suicide attempts. Turban et al. emphasized the importance of having safe and affirming school environments to support transgender and gender diverse students’ mental health.

Counter to providing supportive environments, 33 states proposed over 100 legislative bills that targeted transgender and nonbinary youth in 2021 (Santoro, 2022). These included prohibiting gender-affirming medical care, restricting access to sports, banning transgender youth from using the bathroom corresponding with their gender, denying individuals the ability to change the sex on a birth certificate, and investigating family members and health care providers who assist transgender youth in receiving gender-affirming care. The American Psychological Association has strongly opposed legislation that does not support gender-affirming care stating, “The proposed bills do not align with international standards of care, research, or clinical practice” (Santoro, 2022, p. 52).

College Students:

According to Sax (2010) women enter college with self-reported higher levels of stress and lower levels of emotional and physical health, and these differences continue during the four years of college. Reasons given for a lack of change over the four years include that men spend more time on stress relieving activities, such as sports, video games, partying and watching television. In contrast, women engage in activities that increase stress, such as studying, homework, community services and family responsibilities.

Using data from over 43,000 college students, Borgona et al. (2019) examined mental health differences among several gender groups, including those identifying as cisgender, transgender and gender nonconforming. Results indicated that participants who identified as transgender and gender nonconforming had significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression than those identifying as cisgender. B0rgona et al. explained the higher rates of anxiety and depression using the minority stress model, which states that an unaccepting social environment results in both external and internal stress which contributes to poorer mental health. External stressors include discrimination, harassment, and prejudice, while internal stressors include negative thoughts, feelings and emotions resulting from one’s identity. Borgona et al. recommends that mental health services that are sensitive to both gender minority and sexual minority statuses be available.

Using data from over 43,000 college students, Borgona et al. (2019) examined mental health differences among several gender groups, including those identifying as cisgender, transgender and gender nonconforming. Results indicated that participants who identified as transgender and gender nonconforming had significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression than those identifying as cisgender. B0rgona et al. explained the higher rates of anxiety and depression using the minority stress model, which states that an unaccepting social environment results in both external and internal stress which contributes to poorer mental health. External stressors include discrimination, harassment, and prejudice, while internal stressors include negative thoughts, feelings and emotions resulting from one’s identity. Borgona et al. recommends that mental health services that are sensitive to both gender minority and sexual minority statuses be available.

Adult Women:

Several factors are proposed as to why adult women have higher rates of depression than men. The life time prevalence rate for females is 15.9%, but only 7.7% for males, and these gender differences begin to appear in adolescence (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). Important factors described in the research include that females begin puberty earlier and experience more negative life events, such as sexual abuse and sexual harassment. Additionally, they may possess a somewhat more negative cognitive style, including ruminating on these negative life events. Even while working outside the home, women are over represented in caregiving positions, including caring for children, partners, parents, parents-in-law, and friends (APA, 2018b). The stress of caregiving results in increased mental health issues. Yet, women are repeatedly told they can do it all and they just need to learn how to “juggle” their responsibilities better. Further, the feminization of poverty has also been implicated as there is a strong correlation between poverty and mental health problems. Women who are financially distressed, are single parents, and lack adequate child care demonstrate more depression than women who are financially secure.

Several factors are proposed as to why adult women have higher rates of depression than men. The life time prevalence rate for females is 15.9%, but only 7.7% for males, and these gender differences begin to appear in adolescence (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). Important factors described in the research include that females begin puberty earlier and experience more negative life events, such as sexual abuse and sexual harassment. Additionally, they may possess a somewhat more negative cognitive style, including ruminating on these negative life events. Even while working outside the home, women are over represented in caregiving positions, including caring for children, partners, parents, parents-in-law, and friends (APA, 2018b). The stress of caregiving results in increased mental health issues. Yet, women are repeatedly told they can do it all and they just need to learn how to “juggle” their responsibilities better. Further, the feminization of poverty has also been implicated as there is a strong correlation between poverty and mental health problems. Women who are financially distressed, are single parents, and lack adequate child care demonstrate more depression than women who are financially secure.

Another significant concern for women is the systemic bias in diagnostic assessments. Women tend to be overrepresented in the diagnoses of depression, histrionic and borderline personality disorders, dissociative disorders, somatization disorder, panic disorder, PTSD, and agoraphobia (APA, 2018b). Issues related to the reproductive system, such as menstrual and female sexual disorders, have also been labeled as mental health disorders rather than physical disorders. In addition to these over diagnoses, there is also concern regarding under diagnosis due to gender role biases. A prime example of this is the underrepresentation of females diagnosed with attention-deficit /hyperactivity disorder as it is considered a male disorder.

Adult Men:

According to APA (2018a), “research suggests that socialization practices that teach boys from an early age to be self-reliant, strong, and to minimize and manage their problems on their own yield adult men who are less willing to seek mental health treatment” (p. 3). Internalizing disorders, such as depression and anxiety, are stereotyped as female disorders and consequently males are less likely to be diagnosed with them. This occurs even though males are four times more likely to die of suicide than females. Instead, males are more likely to be diagnosed with externalizing disorders, such as conduct disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and substance use disorders. These externalizing behaviors may actually mask internalizing problems (Pappas, 2019).

Males have higher rates of substance use disorders for alcohol, cocaine, cannabis, and phencyclidine (APA, 2013). Although inhalant-use disorders are comparable among adolescents, adult males are diagnosed more than adult females. For alcohol, the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) (SAMHSA, 2018) indicated that for adults 18 and over, 9.2 million men (7.6 percent of men in this age group) and 5.3 million women (4.1 percent of women in this age group) had an alcohol use disorder characterized by an impaired ability to stop or control alcohol use despite negative consequences. Approximately 62,000 men and 26,000 women die from alcohol-related causes annually, making alcohol the third leading preventable cause of death in the United States. Marijuana use among those 18-25 is increasing for women, but more men continue to use. Trends in marijuana use from 2015-2018 can be seen below.

Adult Gender Minorities:

Gender nonconforming people are much more likely to experience harassment, bullying, and violence based on their gender identity; they also experience much higher rates of discrimination in housing, employment, healthcare, and education (Borgogna et al., 2019; National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Transgender individuals of color face additional financial, social, and interpersonal challenges, in comparison to the transgender community as a whole, as a result of structural racism. Black transgender people reported the highest level of discrimination among all transgender individuals of color. As members of several intersecting minority groups, transgender people of color, and transgender women of color in particular, are especially vulnerable to employment discrimination, poor health outcomes, harassment, and violence. Consequently, they face even greater obstacles than white transgender individuals and cisgender members of their own race. All these obstacles can result in psychological distress that manifests as mental health disorders, including being at an increased risk for suicide attempts: 41% as compared to 1.6% in the general population (APA, 2018b).

Gender nonconforming people are much more likely to experience harassment, bullying, and violence based on their gender identity; they also experience much higher rates of discrimination in housing, employment, healthcare, and education (Borgogna et al., 2019; National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Transgender individuals of color face additional financial, social, and interpersonal challenges, in comparison to the transgender community as a whole, as a result of structural racism. Black transgender people reported the highest level of discrimination among all transgender individuals of color. As members of several intersecting minority groups, transgender people of color, and transgender women of color in particular, are especially vulnerable to employment discrimination, poor health outcomes, harassment, and violence. Consequently, they face even greater obstacles than white transgender individuals and cisgender members of their own race. All these obstacles can result in psychological distress that manifests as mental health disorders, including being at an increased risk for suicide attempts: 41% as compared to 1.6% in the general population (APA, 2018b).

Eating Disorders:

Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2016). Eating disorders affect all genders, although rates among women are 2½ times greater than among men. Similar to women who have eating disorders, men also have a distorted sense of body image, including muscle dysmorphia, which is an extreme desire to increase one’s muscularity (Bosson et al., 2019). Research on gender nonconforming and transgender individuals also indicate increased rates of eating disorders (Diemer, 2018). The prevalence of eating disorders in the United States is similar among Non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics, African–Americans, and Asians, with the exception that anorexia nervosa is more common among Non-Hispanic Whites (Hudson et al., 2007; Wade et al., 2011).

Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: Because of the high mortality rate, researchers are looking into the etiology of the disorder and associated risk factors. Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (NIMH, 2016). Eating disorders appear to run in families, and researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Researchers from King’s College London (2019) found that the genetic basis of anorexia overlaps with both metabolic and body measurement traits. The genetic factors also influence physical activity, which may explain the high activity level of those with anorexia. Further, the genetic basis of anorexia overlaps with other psychiatric disorders. Researchers have also found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with healthy women.

As discussed in module 4, media promotes the “thin ideal” that equates thinness with beauty. How much influence does media exert regarding the development of clinically diagnosed eating disorders? In a recent literature review, Ferguson (2018) concluded that media effects are not as causal as people believe. Rather, Ferguson concluded that real-life influences are more significant that media influences. Individuals are more likely to compare themselves to peers in their social groups than distant media figures they will never meet. In previous research, Ferguson (2013) concluded that women with preexisting body dissatisfaction may be primed by media ideals, and thus be more susceptible. In both reviews, media promoting the thin ideal did not cause eating disorders in women. Further, the muscularity ideal directed toward men, did not result in the development of eating disorders in males.

The main criteria for the most common eating disorders: Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are described in the DSM-5TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) and listed below:

| Anorexia Nervosa | Restriction of energy intake leading to a significantly low body weight

Intense fear of gaining weight Disturbance in one’s self-evaluation regarding body weight |

| Bulimia Nervosa | Recurrent episodes of binge eating

Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain, including purging, laxatives, fasting or excessive exercise Self-evaluation is unduly affected by body shape and weight |

| Binge-Eating Disorder | Recurrent episodes of binge eating

·Marked distress regarding binge eating The binge eating is not associated with the recurrent use of inappropriate compensatory behavior |

Health Consequences of Eating Disorders: For those suffering from anorexia, health consequences include an abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure, which increases the risk for heart failure. Additionally, there is a reduction in bone density (osteoporosis), muscle loss and weakness, severe dehydration, fainting, fatigue, and overall weakness. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder (Arcelus et al., 2011). Individuals with this disorder may die from complications associated with starvation, while others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders.

The binge and purging cycle of bulimia can affect the digestives system and lead to electrolyte and chemical imbalances that can affect the heart and other major organs. Frequent vomiting can cause inflammation and possible rupture of the esophagus, as well as tooth decay and staining from stomach acids. Lastly, binge eating disorder results in similar health risks to obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, heart disease, Type II diabetes, and gall bladder disease (National Eating Disorders Association, 2016).

Eating Disorders Treatment: To treat eating disorders, adequate nutrition and stopping inappropriate behaviors, such as purging, are the foundations of treatment. Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and include medical care, nutritional counseling, medications (such as antidepressants), and individual, group, and/or family psychotherapy (NIMH, 2016). For example, the Maudsley Approach has parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa be actively involved in their child’s treatment, such as assuming responsibility for feeding the child. To eliminate binge-eating and purging behaviors, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) assists sufferers by identifying distorted thinking patterns and changing inaccurate beliefs.

Abortion and Mental Health:

Receiving a wanted abortion does not increase the risk for depression, anxiety or suicidal thoughts. According to Abrams (2022):

More than 50 years of international psychological research show that having an abortion is not linked to mental health problems, but restricting access to safe, legal abortions does cause harm. Research shows that people who are denied abortions have worse physical and mental health, as well as worse economic outcomes than those who seek and receive them. (p. 40)

Rocca et al. (2020) followed 1000 women across 21 states and over 5 years to compare those who obtained an abortion with those who wanted an abortion but were denied. The results indicated that women who had an abortion did not indicate greater negative emotions than those who were denied an abortion, and 97% indicated that having the abortion was the correct decision for them. In fact, five years post-abortion, relief remained the most commonly felt emotion among the women who had an abortion.

What is harmful is harmful to women is a lack of access to an abortion and lack of accurate knowledge about the procedure. Women denied an abortion reported more anxiety and stress, lower self-concept and life satisfaction, more physical problems, worse credit scores, more frequent bankruptcies and evictions, higher chance of living in poverty, and they were more likely to stay with an abusive partner or raise children alone (Abrams, 2022).

The Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling is especially concerning to women with fewer economic resources. For women who live in a state that bans abortion, traveling to obtain one requires money to pay for the traveling expenses in addition to the cost of the procedure. Women living in poverty, women of color, those living in rural areas, and younger women are especially vulnerable to abortion bans in their states (Abrams, 2022).

Older Adults:

Older women are more likely to be living in poverty, experience elder abuse and neglect, and endure more disabilities than older males, which makes them vulnerable to mental health disorders (APA, 2018b). Further, sexism persists and older women experience powerful negative stereotypes regarding their competence, assertiveness, and goals in late adulthood. It is not surprising then that a greater percentage of older females was diagnosed with depression based on scores from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a symptom-screening questionnaire that allows for criteria-based diagnoses of depressive disorders (Brody et al., 2018). As can be seen below, women at all adult ages exhibited higher rates of depression from 2013-2016 than men.

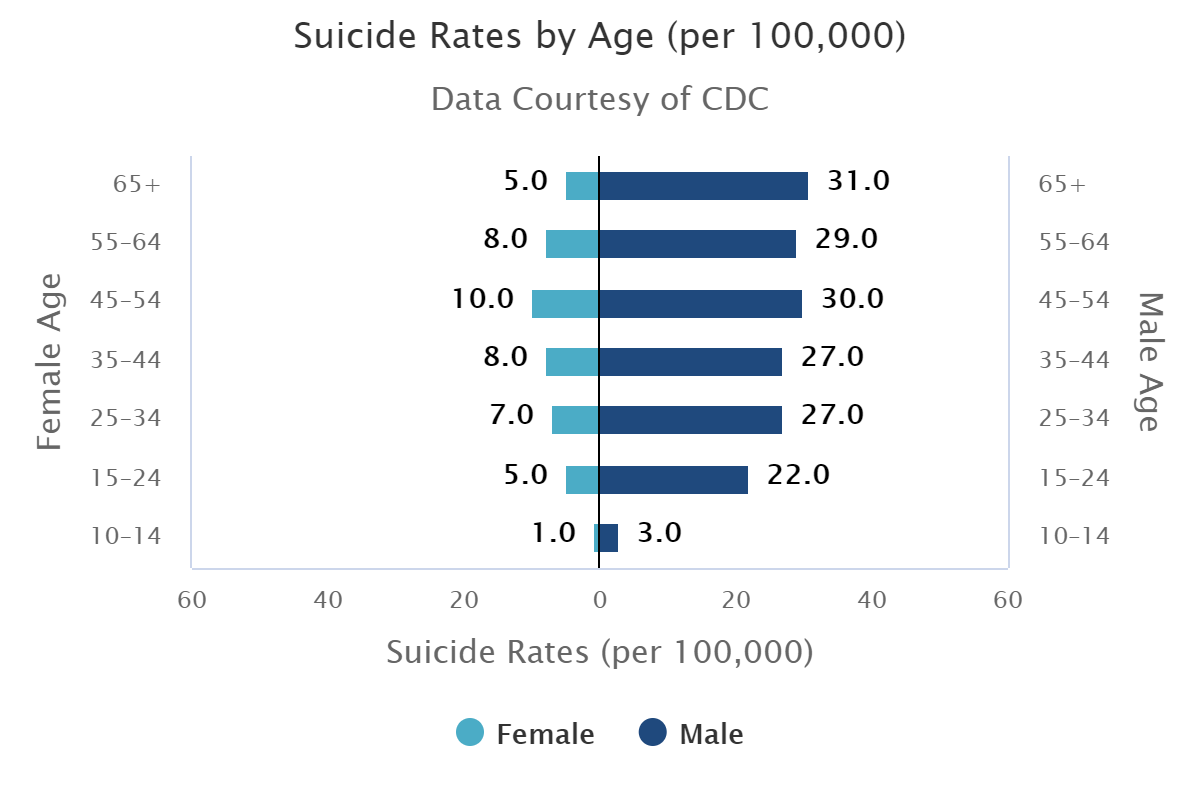

Older males have consistently demonstrated the highest rates of suicide than any other age group for both males and females. In 2018, the suicide rates for males were highest for those 75 and over and increased to 39.9 per 100,000 (Hedegaard et al., 2020). Although females attempt suicide at higher rates than males, males succeed more. Reasons for the higher rate of suicidality for older males are that they typically experience higher rates of substance use disorders, do not seek out mental health treatments, and use more lethal means. Retirement can also be a risk factor for older men who identified as workers and achievers and no longer have that role (Pappas, 2019).

In the final module we will examine the role of gender in aggression and crime. We will consider human aggression overall and why it occurs, the role of social gender roles in fostering aggression, the types of crime committed by and against those in particular gender groups, and incarceration.