Main Body

Module 9 How Does Gender Affect Physical Health?

Case Study: Men and COVID-19

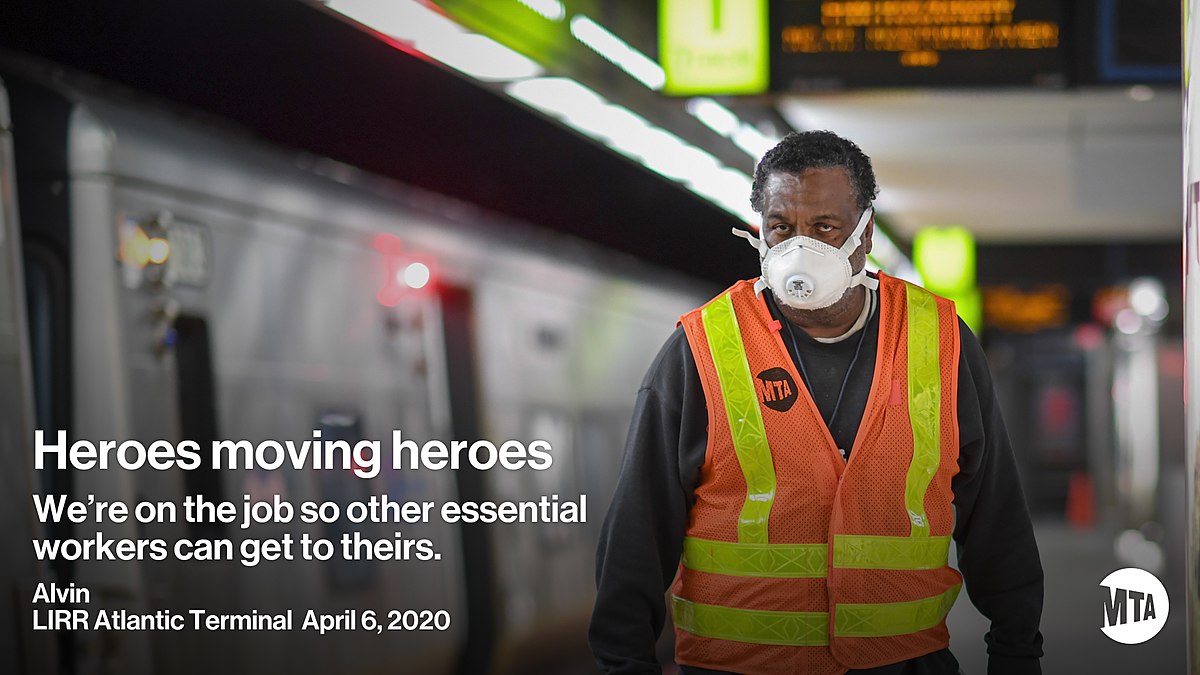

Worldwide data collected since the beginning of COVID-19 shows that men are more likely to have died of COVID-19 in 41 of 47 countries, and the COVID-19 case-fatality ratio is approximately 2.4 times higher among men than among women (Griffith et al., 2020). In the United States, from the beginning of the pandemic until June 2020, 57% of deaths caused by COVID-19 have been men. Reasons given for the gender difference include men being overrepresented as essential workers in low-skilled and low-paid occupations, such as food processing, transportation, delivery, warehousing, construction, and manufacturing. Griffith et al. also indicated that men who are marginalized or disadvantaged because of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, incarceration, or homelessness, have been particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Further, because the X chromosome possesses a higher density of immune-related genes, women are thought to have a stronger immune response compared to men.

Worldwide data collected since the beginning of COVID-19 shows that men are more likely to have died of COVID-19 in 41 of 47 countries, and the COVID-19 case-fatality ratio is approximately 2.4 times higher among men than among women (Griffith et al., 2020). In the United States, from the beginning of the pandemic until June 2020, 57% of deaths caused by COVID-19 have been men. Reasons given for the gender difference include men being overrepresented as essential workers in low-skilled and low-paid occupations, such as food processing, transportation, delivery, warehousing, construction, and manufacturing. Griffith et al. also indicated that men who are marginalized or disadvantaged because of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, incarceration, or homelessness, have been particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Further, because the X chromosome possesses a higher density of immune-related genes, women are thought to have a stronger immune response compared to men.

Behavioral factors traditionally associated with men are also linked with higher rates of contracting COVID-19. Reny (2020) attributes these behaviors to men following masculine norms that encourage risky behavior and discourage seeking out physical and mental health services. These high risk behaviors demonstrated more by men include: Downplaying the severity of the virus’s potential to harm them, being less likely to avoid large public gatherings or close physical contact with others, engaging in higher rates of tobacco use and alcohol consumption, and engaging in less handwashing, social distancing, mask wearing, and proactively seeking medical help (Griffith et al., 2020; Reny, 2020).

Holding sexist beliefs were also reported as a factor. Using data from a large (N = 100,689) survey of American adults conducted between March and June 2020 by the Democracy Fund and the University of California, Los Angeles, Reny (2020) found that, “sexist beliefs were consistently the strongest predictor of corona virus related emotions, behaviors, policy attitudes, and ultimately contracting COVID-19,” (p. 1). Sexist opinions included an affirmation of men’s elevated position in social hierarchies and a belief in the biological superiority of men over women. Sexist individuals were not as worried about the virus, engaged in behaviors less likely to protect themselves, were less likely to support state and local government policies enacted to stop the spread of the disease, and were more likely to get sick themselves.

Life Expectancy

The oldest man to have lived was Jiroeman Kimura who died when he was 116 years, 54 days. Eighteen women have exceeded that age, with Jeanne Calment being the oldest at 122 years, 164 days. Among the top 100 Americans to have lived, the top nine are women, and among those in the list who are still alive, all five are women. Around the world, women outlive men. Are the gender differences in longevity due to something biological or environmental? As with most issues regarding gender differences both are likely to influence longevity.

Life expectancy is defined as the average number of years that members of a population (or species) live. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2019) global life expectancy for those born in 2019 is 72.0 years, with females reaching 74.2 years and males reaching 69.8 years. Women live longer than men around the world, and the gap between the sexes has remained the same since 1990. Overall life expectancy ranges from 61.2 years in the WHO African Region to 77.5 years in the WHO European Region. Global life expectancy increased by 5.5 years between 2000 and 2016. Improvements in child survival and access to antiretroviral medication for the treatment of HIV are considered factors for the increase. However, life expectancy in low-income countries (62.7 years) is 18.1 years lower than in high-income countries (80.8 years). In high-income countries, the majority of people who die are old, while in low-income countries almost one in three deaths are in children under 5 years of age. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (2019) the United States ranks 45th in the world for life expectancy.

A better way to access health and longevity is to go beyond chronological age and examine how well the person is aging. The Healthy Life Expectancy takes into account current age-specific mortality, morbidity, and disability risks. In the U.S., the highest Healthy Life Expectancy (HLE) was observed in Hawaii with 16.2 years of additional good health after age 65, and the lowest was in Mississippi with only 10.8 years of additional good health (CDC, 2013). Females had a greater HLE than males at age 65 in every state and DC. HLE was greater for whites than for blacks in DC and all states from which data were available, except in Nevada and New Mexico. Although improvements have occurred in overall life expectancy, children born in America today may be the first generation to have a shorter life span than their parents. Much of this decline has been attributed to the increase in sedentary lifestyle and obesity. Since 1980, the obesity rate for children between the ages of 2 and 19 has tripled (Henry, 2016).

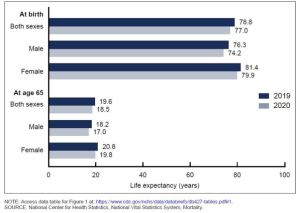

More recently COVID-19 has altered the statistics of life expectancy, especially in the United States, which faired worse than 16 comparable nations, with the life expectancy dropping at a rate not seen since the second World War (Woolf, 2021). The figure to the left shows CDC data comparing 2019 to 2020 and indicates that life expectancy at birth dropped 1.8 years, with males losing 2.1 years, and females losing 1.5 years (Murphy et al., 2021). Among those who had already reached 65, the gender difference is less pronounced, with males losing 1.2 years and females 1 year.

Causes of Death in the United States:

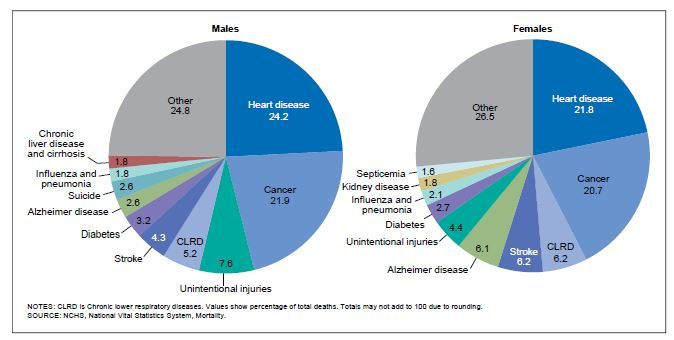

When reviewing the leading causes of death in the United States, males have higher death rates than females in every age group, and sex differences in biology and risk-taking are largely responsible for this discrepancy (APA, 2018a). Listed below are the leading causes of death for men and women in the Unites States in 2017, the most recent year the data has been analyzed (Heron, 2019). Heart disease and cancer are the leading causes of death in both men and women. However, men and women differ in the rankings of many of the other leading causes. For example, dying from unintentional injuries was the third leading cause of death in men, but the sixth leading cause for women. In contrast, chronic lower respiratory disease was the third leading cause of death for women, but fourth in men. Suicide and liver disease do not show up in the top ten causes of death of women, but do for men. Kidney disease and septicemia are among the top ten killers of women, but not men.

The morbidity-mortality paradox describes how women have higher rates of chronic, nonfatal, but debilitating health problems, such as arthritis, autoimmune disorders, and osteoporosis than men, yet tend to live longer than men. When asked to assess their overall health as either excellent, good, fair, poor, or bad, women are more likely to provide a lower evaluation than men in all ages and in all regions of the world (Boerma et al., 2016). Some have suggested that this gender gap may be the result of women underestimating their health, however, the evidence supports women’s self-reports. As noted above women are more likely to suffer from chronic painful conditions. Others have suggested that this gender difference may be the result of men being overconfident in their assessment of their health, or unwillingness to admit to poor health (Bosson et al., 2019). While this may be true, as men’s overconfidence has been noted in other aspects of their life, it may reflect the nature of the samples in the survey research and men’s comparison group. Most samples in studies on chronic illness are likely to trend toward older populations where there are fewer males. Men who have already outlived many of their peers may think themselves pretty healthy in comparison.

Role of Biology in Gender Differences in Health and Longevity:

Humans are not the only species where females outlive the males (Kawahara & Kono, 2010). This is common in many mammals and even other species. When a gender difference is found in the longevity of a species, it usually favors the female. This would suggest that biological factors are playing a role in longevity. Kawahara and Kono genetically engineered female mice so that they received their genetic material from two females, meaning they had two mothers but no fathers. The result was mice that lived even longer. They concluded that the female genome plays a role in longevity and that “the sperm genome has a detrimental effect on longevity in mammals” (p. 457).

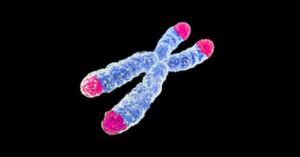

Another biological advantage for females may come from the final pair of chromosomes. As you learned in module 3, females have two X chromosomes, whereas males have only one X that is paired with a much smaller Y chromosome. Prenatally, males have a higher death rate (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). At conception the ratio of male to female zygotes is approximately 120:100, but at birth the ratio is 105:100. Sex-linked genetic defects appear to be the cause. The X chromosome contains genes that influences many important body functions. A defect on one X chromosome might be overridden if a person has a normal second X chromosome. But in males who have only one X, they are much more vulnerable to that defect. As a result, male are at greater risk for x-linked diseases such as fragile X syndrome, hemophilia, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

At the end of each of our 46 chromosomes are segments of genetic material that do not code for any particular trait or characteristic. These segments, called telomeres, are disposable DNA that protect the genes on the chromosomes. Each time a cell divides it fails to copy some of the DNA material at the end of the chromosome, meaning these telomeres get shorter and shorter. Eventually the cell can no longer divide and it dies. Scientists are learning that shorter telomeres also show up along with certain diseases, like atherosclerosis and some types of cancer (Srinivas et al., 2020). According to Srinivas and colleagues, it is suspected that shorter telomeres also compromise the health of cells in blood vessels, which may set the stage for clots to form, stick, and block blood flow. Despite length of the telomeres being the same for males and females at birth, the telomeres of males shorten faster with each cell division. Male cells age faster (Barrett & Richardson, 2011) and may also set the stage for certain diseases. It is possible that this might play a role in the greater longevity of females, whether they are humans, mice, or angler fish.

At the end of each of our 46 chromosomes are segments of genetic material that do not code for any particular trait or characteristic. These segments, called telomeres, are disposable DNA that protect the genes on the chromosomes. Each time a cell divides it fails to copy some of the DNA material at the end of the chromosome, meaning these telomeres get shorter and shorter. Eventually the cell can no longer divide and it dies. Scientists are learning that shorter telomeres also show up along with certain diseases, like atherosclerosis and some types of cancer (Srinivas et al., 2020). According to Srinivas and colleagues, it is suspected that shorter telomeres also compromise the health of cells in blood vessels, which may set the stage for clots to form, stick, and block blood flow. Despite length of the telomeres being the same for males and females at birth, the telomeres of males shorten faster with each cell division. Male cells age faster (Barrett & Richardson, 2011) and may also set the stage for certain diseases. It is possible that this might play a role in the greater longevity of females, whether they are humans, mice, or angler fish.

A final biological answer may be found in hormones. Testosterone, which is typically higher in men, increases aggression and risk taking. It also decreases the level of “good” cholesterol while increasing the level of “bad” cholesterol (Vanberg & Atar, 2010). Testosterone also suppresses the immune system, which might account for women’s greater ability to fight infections (Furman et al., 2014). In contrast, women typically have higher levels of estrogen. Estrogen provides more health benefits. Prior to menopause, when women have higher levels of estrogen, they have a lower risk of cardiovascular disease compared with men the same age (Xue et al., 2013). However, estrogen can increase the risk for certain forms of cancer (Srinivas et al., 2020).

Role of Environmental Factors in Male Health and Longevity:

Behaviorally, males with the strongest beliefs regarding masculinity were half as likely as men with more moderate beliefs to obtain preventative health care (Pappas, 2019). Additionally, the more men conformed to traditional masculine roles, the more likely they considered heavy drinking, smoking, and avoiding vegetables as normal. Lung cancer and heart attacks, linked to cigarette smoking, are higher in males, as is cirrhosis of the liver due to excessive drinking (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). Auto accidents claim more male lives as 71% of motor vehicle deaths are males due to their driving more, driving faster, and taking more risks. Lastly gun deaths, which will be discussed more in module 10, result in more male deaths. Overall, men who exhibit more masculine traits die younger than those identified as less masculine.

Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Health

Some diseases and their gender, racial and ethnic differences: (adapted from American Cancer Society, 2020; American Lung Association, 2020; CDC, 2017; Le, 2016; Mamary, et al., 2018; McLeod et al., 2014; NIH, 2020; National Kidney Foundation, 2020; Pappas, 2019; Regitz-Zagrosak, 2012; Spencer-Scott, 2020; Stojan & Petri, 2018).

- Women are affected by all forms of anemia more than are men, with iron deficiency being the most common cause. The highest rate of anemia is found for elderly black women, who have over six times the national average.

- Thyroid disease is more common in women, but thyroid cancer is more common in men. Graves disease is more common in Blacks.

- Overall, more men develop cancer than do women, but that gap is narrowing. Prostate cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed among U.S. men of all races and ethnic groups. The most common cancer diagnosed among U.S. women is breast cancer, but lung cancer is the leading cause of death among cancers in women of all races and ethnic groups except Hispanic women, for which breast cancer is the leading killer. Females appear to be at higher risk of developing lung cancer than males if they smoke.

- Women are more likely than men to get lupus for every age and ethnic group, but men are more likely to have more severe symptoms. World wide epidemiological studies show that people of African ethnicity have the highest incidence of lupus, whereas those with Caucasian ancestry had the lowest incidence.

- There is a higher incidence of asthma in boys, but by young adulthood it is more prevalent in women and the symptoms are often more severe. Blacks and American Indian/Alaska Natives have the highest asthma rates, while Hispanics and Asians have the lowest overall prevalence.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a progressive lung disease in which the airways become damaged making it difficult to breathe, was once considered a “man’s disease”. However, in the last 20 years 58% of those with COPD are women, in part because the lungs of women are more vulnerable to effect of smoking. Race impacts the rate of diagnosis and treatment of COPD.

- Men experience diabetes at slightly higher rates than women, but it is more likely to cause myocardial infarction (a form of heart disease) in women than in men. Diabetes also varies by race with non-Hispanic Whites being less likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than Asian Americans, Hispanics, non-Hispanic Blacks, and American Indians/Alaskan Natives.

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack) is in decline around the world, except in young women. Young women are more likely to die from their first heart attack, and from the bypass surgery than are young men. Women, of all ages, are also more likely to present with more varied symptoms, making diagnosis and treatment difficult. Non-Hispanic Blacks are more likely to die from a heart attack, even though they have slightly lower rates of heart disease than non-Hispanic Whites.

- Hypertension (high blood pressure) is more common in young men than in young women, but this incidence increases after menopause in women. For African American males, systemic racism interacting with the masculine traits of stoicism and providing for one’s family, has been linked to hypertension.

- Women are three times more likely to have autoimmune disorders and three times more likely to experience headaches and migraines than men.

- Women are more likely to have kidney disease as they age and experience more complications from it than men. Black or African Americans are almost 4 times more likely, and Hispanics or Latinos are 1.3 times more likely to have kidney failure compared to White Americans.

- Gout, a common form of inflammatory arthritis caused by excess uric acid in the bloodstream, is more common in men.

- The severity of osteoarthritis is usually significantly worse in women than in men. However, before age 45, more men than women have osteoarthritis, but after age 45, the condition is more common in women. Black women are at greater risk than white women for developing osteoarthritis and for experiencing complications from the condition.

- Men fall ill at a younger age, have more illnesses in their lifetime, and cost society more in medical costs after the age of 65 than women. Black men have poorer health compared to other demographic groups, and possible reasons are discussed below.

Latinx paradox refers to a tendency of Latinx Americans to have as good, if not better, health than non-Latinx White Americans despite having less education and a lower socioeconomic status. Typically those with less education and income tend to have poorer health. While researchers do not fully understand this paradox, several hypotheses have been proposed regarding diet, family ties, and having less sedentary occupations. Moreover, this health advantage does decline the more the Latinx population adopts the American lifestyle (Gonzalez, 2015).

Black Men

The health of black men consistently ranks lowest across nearly all groups in the United States (Gilbert et al., 2016). On average, black men die younger than all other groups of men, except Native Americans, and they die more than seven years earlier than women of all races. Even as mortality and morbidity have improved in the United States, black men remain more likely to die from cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancers. Black men are also more likely than others to have undiagnosed or poorly managed chronic conditions and to delay seeking medical care. Additionally, fewer black men have a usual source of health care (Stewart et al., 2019). The relatively lower socioeconomic status of black men compared with white men, or any differences in patterns of health behaviors, do not explain all the differences (Gilbert et al., 2016). In addition to economic reasons, implicit bias among health care providers has been identified as a significant factor resulting in poorer medical outcomes for Black men and women (Dembosky, 2020; Hall et al., 2015; Schencker, 2020).

The term implicit bias was created by Greenwald and Banaji (1995) to explain how social behavior is largely influenced by unconscious associations and judgments. These unconscious biases can lead to discriminatory practices. According to Schencker (2020), implicit bias that negatively affects the health care of people of color has been well-documented. Examples of implicit bias include medical personnel adopting a more closed posture and exhibiting reduced eye contact with nonwhite patients. Physicians who are more implicitly biased spend less time with Black patients, are less patient-centered, show less empathy, and spend less time assessing their medical symptoms. Black patients are less likely to receive pain medication or be referred for additional care than white patients with the same symptoms (Dembosky, 2020). Doctors may also implicitly associate Blacks with self-destructive behaviors, such as drug abuse. Black patients are often aware of this bias and may not trust their physicians, listen to health recommendations, or return for follow-up care, adversely affecting their health.

LGBT Physical Health

Those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) come from all walks of life, include all races and ethnicities, ages, and socioeconomic statuses. In addition, members of the LGBT community are at increased risk for a number of health threats when compared to their heterosexual peers (CDC, 2014). The social and structural inequities, such as the stigma and discrimination that LGBT populations experience, along with increased risk of HIV play a large role in this health disparity.

Lesbians

For women, those who identify as lesbian and bisexual have higher rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, asthma, and obesity (Dilley et al., 2010). Additionally, they are less likely to access preventive screenings, such as Papanicolaou (pap) tests and mammograms. According to Boehmer et al. (2007), lesbians have more than twice the odds of being overweight and obese compared to heterosexual women. Boehmer et al. referenced previous research explanations for the increased weight, including that lesbians are less likely to consider themselves overweight compared with women in the general population. Lesbian women also have a better body image than do heterosexual women, and they are more likely to prioritize a body image on the basis of physical function and not aesthetic reasons.

Mereish (2014) found that being overweight or obese was more likely for lesbians who experienced heterosexist discrimination than normal-weight lesbians. The frequency lesbians experienced discrimination, specifically related to their sexual minority status at work, in school, and in other areas of their life, was correlated with their odds of being overweight. Mereish explained that chronic exposure to minority stressors, such as heterosexist discrimination, can result in increased cortisol levels, thus elevating one’s risk for obesity. Exposure to discrimination may result in less effective coping strategies, including stress eating. Additionally, lesbians may be reluctant to seek health care services due to potential or perceived heterosexist discrimination from medical providers. Regardless of the reasons, being overweight and/or obese places sexual minority women at an increased risk for medical conditions associated with an elevated risk for suffering or death (Boehmer et al., 2007).

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV):

HIV is a virus that weakens a person’s immune system by destroying important cells that fight disease and infection (CDC, 2020). No effective cure exists for HIV. But with proper medical care, HIV can be controlled.

Prevalence

In the Unites States in 2018, the most recent data that has been analyzed, the rate of HIV infection was 11.4 per 100, 000 people (CDC, 2019). The highest rate (32.5) was for persons aged 25–29 years, followed by the rate (27.6) for persons aged 20–24 years. The rates for children, teens, middle aged adults, and seniors decreased from prior years. While the rate for young adults in their 30s remained the same. Males accounted for 81% of all diagnoses of HIV infection among adults and adolescents, with a rate four times higher than females. Blacks/African Americans had the highest rate, with Asians having the lowest. The highest rates of HIV infection were in Southern states and the lowest rates were in the Midwest.

|

Rate of HIV Infection by Gender and Race/Ethnicity |

|

| Social Category | Rate per 100,000 |

| Male | 22.5 |

| Female | 5.1 |

| Black/African American | 39.3 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 16.2 |

| Multiple Races | 12.4 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 11.8 |

| American Indian/Alaska Natives | 7.8 |

| White | 4.9 |

| Asian | 4.7 |

AIDS:

The rate of stage 3 HIV (AIDS) in 2018 was 5.2 per 100,000 people in the US (CDC, 2019). The highest rate (10.9) was for persons aged 30–34 years, followed by 10.3 for persons aged 35–39 years. Males account for 76% of all stage 3 HIV infections among teens and adults, with the male rate being more than three times higher than that for females. While the rate of AIDS decreased for Black/African Americans, it was still the highest of all racial and ethnic groups (19.6), with Asians (1.8) being the lowest.

The most common means of HIV transmission among males were male-to-male (70%) and heterosexual sexual contact, while among females the most common reasons were heterosexual contact (85%) and injection drug use (CDC, 2019). This pattern was consistent across different racial and ethnic groups.

Factors Affecting Diagnosis, Care, and Treatment:

There are several factors that influence risk of HIV, the care people with HIV receive, and access and adherence to treatment. As the data above suggest, engaging in unprotected sex with men and injection drug use increase people’s risk. However, these are not the only risk factors.

Gender-based violence, which is violence against an individual based on their gender or gender identity, has been shown to increase risk for HIV, as well, as impeding access to testing, care, and treatment (Leddy et al., 2019). Female sex workers, transgender women, and other gender minorities face substantial disparities when it comes to health, including risk for, and treatment of, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI) (Leddy et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2018). Nguyen and colleagues found that were was no consistency in how states and counties in states reported the number of cases of a STI by gender status beyond the gender binary of male and female. As a result, the rates of infection of gender minorities are often hidden in the aggregate data. This could hamper public health outreach programs to some of the most vulnerable members in communities.

In the United States there are racial and ethnic disparities when it comes to the diagnosis, treatment, and care of HIV (Bogart et al., 2018). As previously shown, the rate of HIV in Whites and Asians is two to four times lower than found in other racial and ethnic groups (CDC, 2019). According to the CDC (2020), several factors may work against prevention, testing, and treatment initiatives. Both the Black and Latinx community experience high levels of distrust of the health care system (CDC, 2020). This can reduce the likelihood of clinic visits and result in less adherence to antiretroviral treatments. While not unique to minority cultures, stigma, discrimination, and homophobia may also play a role in people’s unwillingness to discuss prevention, seek a test, or get treatment from their doctor.

This disparity is even greater when adding in sexual or gender minority status. For example, HIV-positive Black gay and bisexual males’ experiences with both racial and sexual discrimination is associated with lower adherence to treatment, increased symptoms of depression, and greater need to be admitted to an emergency room due to worsening health (Bogart et al., 2018).

Racial and ethnic disparities in the rates of infection have often been attributed to risky behaviors such as, drug and alcohol use, or the number of sexual partners. However, even when these factors are controlled for, African Americans still have a higher risk of HIV infection in comparison to other racial and ethnic groups (Gibson et al., 2018). In their study in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Gibson and colleagues found that regardless of racial or ethnic group, poverty was a better predictor of rates of infection. Eighty percent of the newly diagnosed rates of infection were in the highest poverty areas of the city. This study also found that the highest HIV mortality rates were for African American men who lived below poverty. This finding is consistent with prior research on the contribution of socioeconomic inequities to access to health care and mortality, in general (Mode et al., 2016).

Cancer:

The most common types of cancer among women are skin, breast, lung, colorectal, endometrial (uterine), and cervical cancer. Lesbian and bisexual women may be at increased risk for some cancers, including breast, cervical, and ovarian cancer compared with heterosexual women (American Cancer Society, 2020). Women who have not had children or have not breast-fed are at a slightly higher risk of breast cancer. These factors may be more likely to affect lesbian and bisexual women. Lung, cervical, and ovarian cancer risks may be higher in lesbian and bisexual women as there is evidence to suggest that they are about twice as likely to smoke compared to heterosexual women (American Cancer Society, 2020).

Gay and bisexual males have the same risks of lung, prostate and testicular cancer as heterosexual males, however they are at a heightened risk for anal cancer. The risk factors for anal cancer include the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can spread through sexual activity, including oral and anal sex. Even skin-to-skin contact with an infected area can spread the virus. Smoking is another risk factor for anal cancer. However, what puts gay and bisexual males at an even greater risk is a weakened immune system because of HIV (American Cancer Society, 2020).

Seeking and Receiving Health Care

Women are more likely to seek medical treatment for both medical and mental health than are men, even when accounting for health care needs that are unique to women (Thompson et al., 2016). According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

- Men are 24 percent less likely than women to have visited a doctor within the past year and are 22 percent more likely to have neglected their cholesterol tests.

- Men are 28 percent more likely than women to be hospitalized for congestive heart failure.

- Men are 32 percent more likely than women to be hospitalized for long-term complications of diabetes and are more than twice as likely as women to have a leg or foot amputated due to complications related to diabetes.

- Men are 24 percent more likely than women to be hospitalized for pneumonia that could have been prevented by getting an immunization.

Thompson and colleagues also found that women often reported longer consultations with their doctor than did men. Men who endorse more traditional views of masculinity are more likely to hold off seeking treatment (Himmelstein & Sanchez, 2016), which can lead to greater complications with their health. In addition, Himmelstein and Sanchez found that these men are more likely to want a doctor who is male because they believe he would be more competent than a woman. However, in health consultations men reveal more about their health when the doctor is female. This suggests that gender role norms play a role in willingness to seek health care, and may increase the risk of an untreated illness.

However, seeking health care is also influenced by characteristics such as age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and being LGBTQ+. Older women and men see doctors more than do younger women and men, often because of the presence of chronic illness (Thompson et al., 2016). Black and Latinx males are less likely to have a primary care provider than are White males (McFarlane & Nikora, 2014), thus less likely to seek treatment. In the U.S. those without medical insurance are less likely to seek health care. Despite the known health risks for members of the LGBT community, screening rates are often low for cancer and other health concerns, and there are gaps in the recommendations for screening for LGBT persons (Ceres et al., 2018).

Even where in the nation people reside can impact the rates of seeking and receiving treatment. There are significant differences in the healthcare access in rural and urban America (Douthit et al., 2015). In rural areas there is a greater reluctance to seek healthcare often based on cultural and financial constraints. In addition, a scarcity of resources, being able to maintain trained physicians, and poor transportation options only compound the issue. As a result, rural Americans have poorer overall health. Barefoot et al., (2017) found that lesbians living in rural America, in comparison to their urban counterparts, may experience elevated health risks. They were more likely to report having had at least one previous male sexual partner (78% compared to 69%), but were less likely to be recommended the HPV vaccination by their doctor and engaged in lower rates of regular HIV/STI screenings. Rural lesbians were less likely to have received Pap tests and clinical breast exams. For those 40 or older, they were less likely to receive routine mammogram screenings. Both Douthit et al. and Barefoot et al., suggest that there is a need to engage rural residents and healthcare providers in health promotion.

Trust in doctors also plays a role (Thompson et al., 2016). Black Americans report less trust in doctors than do White Americans. This lack of trust is understandable given the experiences that Blacks, and Black men in particular, have had with the medical community. In what came to be known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, from 1932 to 1972 in Alabama, hundreds of poor, illiterate Black men with syphilis were given a placebo rather than the known treatment for the disease, penicillin, so doctors could see the progression of untreated syphilis (Gamble, 1997). The study was eventually halted in 1972 due to its questionable ethnics, and in 1997 President Bill Clinton issued a public apology to the men affected by the study. However, the damage had already been done to sour the view of Blacks in this country toward the medical community.

Trust in doctors also plays a role (Thompson et al., 2016). Black Americans report less trust in doctors than do White Americans. This lack of trust is understandable given the experiences that Blacks, and Black men in particular, have had with the medical community. In what came to be known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, from 1932 to 1972 in Alabama, hundreds of poor, illiterate Black men with syphilis were given a placebo rather than the known treatment for the disease, penicillin, so doctors could see the progression of untreated syphilis (Gamble, 1997). The study was eventually halted in 1972 due to its questionable ethnics, and in 1997 President Bill Clinton issued a public apology to the men affected by the study. However, the damage had already been done to sour the view of Blacks in this country toward the medical community.

Trust is also a factor in the willingness of sexual and gender minorities in seeking treatment (American Cancer Society, 2020). Fear of discrimination by the medical community is an important barrier to seeking and receiving treatment. For example, it is often not easy to find a healthcare provider who knows how to treat transgender people, or to even find someone who will agree to treat such patients (Allison, 2012). Doctors and nurses are not immune to the stereotypes that abound in the culture.

People who seek routine health care, develop a rapport with their doctor and become more comfortable talking about their health. This makes future visits more likely. Health care visits also increase the chance that unknown problems may be detected, or detected early. Moreover, disclosure of mental health concerns during routine care is often the main route toward receiving referrals for mental health treatment. When patients do not trust the medical system, none of this is likely to occur.

Medicalization of Reproduction

Medicalization is the process where more normal functions of the body come under medical influence, and treatments emerge for what were previously viewed as non-medical problems (Shainwald, 2014; Waggoner & Stults, 2010). The biomedical approach emphasizes basic biology (e.g., genes, hormones) in illness and excludes contextual factors such as relationships, identity, community, and culture in both health and illness (McHugh & Chrisler, 2015). Moreover, experts and representatives from the pharmaceutical industry serve on the very government panels, task forces, and professional associations that set the criteria for defining illness and disease. An important caveat to make is that medicalization is not the same as the science and practice of medicine. Medical researchers and doctors have contributed greatly to the health and well-being of people. However, driven by profit, medicalization has damaged the integrity of medical science through funding only the more profitable research questions, and in focusing on drugs to deal with life style problems rather than curing illness (Abramson, 2004). The end result is that “functions have become symptoms, and symptoms have become diseases” (Shainwald, 2014, para 10). There are numerous medical interventions for normal female reproductive functions, such as the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, birth, and menopause.

Menstruation:

Menstruation is a stigmatized reproductive event. “It’s something polite society normally never speaks about in public. In fact, such is the studied avoidance of the subject of menstruation that one would think it wasn’t something that happened to one half of the world’s population for four-six days every month” (Gupta, 2015, para 1). When society does refer to menstruation, we often use words such as the “crimson tide”, the “curse”, or “code red”. Globally, social norms, attitudes, and beliefs relating to menstruation vary widely, and these variations impact women and girls. For example, people in some settings believe that menstruation is dirty and that menstruating women are unclean. This can lead to restrictions, such as seclusion from others, dietary restrictions, and being prevented from full participation in the community (Mohamed et al., 2018). Moreover, the inability to manage menstrual bleeding at school or the workplace in some parts of the world can lead to long-term consequences for economic and health outcomes for women and girls.

Today, some scientists and medical professionals view menstruation as unnecessary, and often discuss the negative effects some women may experience. From this viewpoint, menstruation is something that is harmful and needs treatment. This view was strongly illustrated by Coutinho and Segal’s book, Is Menstruation Obsolete? To support their view they emphasized disorders, such as endometriosis, premenstrual syndrome, and anemia, and the negative impact these problems have on women’s well-being. According to Coutinho and Segal, they set out to educate women on how to suppress menstruation. What was not clearly stated was how both men stood to gain financially, as they were both involved in the creation of methods used to suppress menstruation (Barnack-Tavlaris, 2015).

Opponents of this view have raised the concern that women who are suppressing their menstrual cycle through the use of a continuous oral contraceptive can be exposed to 25% to 33% more estrogen than a traditional oral contraceptive (Barnack-Tavlaris, 2015). Research already shows that women who use traditional oral contraceptives have a slightly higher risk (7%) of breast cancer, and a 2017 study reported that a 20% increase was associated with more recent formulations of oral contraceptives (National Cancer Institute, 2018). Opponents also argue that it is misleading to use disorders related to menstruation to justify the suppression of menstruation in all women (Barnack-Tavlaris, 2015). Menstruation, itself, is not a disorder. It is a normal body function that some elements in the medical community have defined as a disease.

Pregnancy and birth:

One of the most powerful things the female body can do is to become pregnant and give birth. Yet, increasingly this has become medicalized in developed nations. Several changes in how we view pregnancy has been the result of this medicalization and a growing concern is that it may “alienate women from their bodies” (Bosson et al., 2019, p. 437). Home pregnancy tests hasten women’s involvement with obstetricians, and into the role of “patient” (Tone, 2012). The use of ultra-sounds during low-risk pregnancies may exaggerate women’s perception of risk and danger during pregnancy, and may not always improve outcomes (Fisher et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2016).

For generations, women gave birth at home with a mid-wife or other female relatives present. This has been replaced by hospitals and doctors. In 2017, 1.6% of births were an out-of-hospital birth (MacDorman & Declercq, 2019). Hospitalized births may create the view that childbirth is high risk and requires expert care. A controversial consequence of the medicalization of pregnancy is the overuse of interventions and treatments during delivery. Fetal heart monitoring, epidurals, episiotomies, and ultra sounds are becoming increasingly a routine part of childbirth. Besides adding to the financial cost of childbirth, there is little consensus that these procedures are always necessary (Bosson et al., 2019).

In the United States, one in three babies are born by cesarean section (c-section) a surgery used to deliver the baby through the mothers’ lower abdomen (MedlinePlus, 2020). In 1970, only about 6% of births were via cesarean. In the U.S. that number varies by region, as if women’s organs differ on the basis of geography. In Hawaii it is about 22% (lowest rate), while in Mississippi (38%) it is jokingly referred to as the “Mississippi appendectomy” (Shainwald, 2014).

| Rate of Cesarean in Selected States in 2018 (CDC, 2020) | |

|---|---|

| Illinois | 31% |

| Hawaii | 22% |

| Wisconsin | 27% |

| Mississippi | 38% |

This increase in the use of c-sections is not just happening in the U.S. Several developed nations show the same trend, with some nations (e.g., China) reporting rates as high as 50% of births (Bosson et al., 2019). As a major surgery, cesareans carry all the same risks as other major surgeries.

Since ancient times some women’s pregnancies have ended early. From the standpoint of the medicalization of pregnancy, such pregnancies indicate a flaw in the functioning of women’s bodies, and such flaws can be ameliorated via medical intervention. In fact, a growing number of those preterm births are the result of surgeries and other medical interventions in pregnancies where there are complications (Bronstein, 2020). As Bronstein writes, “the popular cultural narrative holds that preterm births are preventable, provided pregnant women “take care of themselves” and follow medical advice” (p. 235). This places the responsibility for carrying a pregnancy to term solely on the mother. One preventative intervention often prescribed by doctors is complete bed rest. Yet research has repeatedly shown that it does little to prevent preterm birth, and it has a negative impact on the mother’s health and well-being.

Menopause:

Menopause has been medicalized since the 1930s (Waggoner & Stults, 2010) and is viewed as a deficiency from the biomedical model (Shainwald, 2014). As a result women are expected to take medications and supplements to maintain childbearing levels of hormones rather than age normally.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) is medication that contains female hormones, taken to replace the estrogen that the female body stops making during menopause (Mayo Clinic, 2020). Hormone therapy is most often used to treat common menopausal symptoms, including hot flashes and vaginal discomfort. The initial claims for HRT was to keep women “feminine forever” and to decrease the risks of heart disease, osteoporosis, and breast cancer. In 2001, HRT was prescribed to more than 15 million women in the U.S. However, with the termination of Women’s Health Initiative trial in July of 2002 due to increased risk of breast cancer, heart disease, and blood clots in the HRT group, prescriptions for oral estrogen dropped 43% (Waggoner & Stults, 2010), and left many women in limbo about whether HRT was right for them, or were they at risk now because they had been using these medications.

Erectile dysfunction:

Men also experience the medicalization of reproduction, although to a lesser degree. With the introduction of Viagra in 1998, which helps men achieve and sustain an erection, erectile dysfunction (ED) became a medicalized issue. Direct to consumer advertising made Viagra one of the top selling drugs. In 2019, Viagra generated $500 million for Pfizer (Mikulic, 2020) despite there now being a number of competitors and generic versions of the drug. Advertising has also expanded the market beyond erectile dysfunction by portraying Viagra as an enhancement targeted to younger men (Waggoner & Stults, 2010).

Double Standard of Aging:

The double standard of aging refers to the idea that men’s social value increases with age, while women’s declines. Nolan and Scott (2009) found that women are viewed as being “old” at a younger age than are men. Clarke and Griffin (2008) report that women see aging as having a more negative impact than do men. Many reported feeling invisible in a culture that emphasizes youth and appearance for women. While men reported feeling more distinguished in their appearance as they aged. However, other research show the opposite effect for ratings of competence. For instance, as men age people rate men’s competence as declining, while this is not true for people’s ratings of women (Kite et al., 2005). Men also express more concern about their physical health and capabilities as they age (Nolan & Scott, 2009). Aging affects men and women in the areas that are relevant to their gender roles; appearance for women, and competence for men.

Politicization of Reproduction

Abortion : A brief history in America leading up to Roe v. Wade

For much of the early 19th century, abortion was legal up to the point where the mother could feel the fetus move, the quickening; typically, between 14 and 26 weeks (Gold, 2003). Abortions were usually performed by homeopaths and midwives. By the end of the 19th century, abortion was illegal in most U.S. states, except if it was dangerous to the mother’s health to continue with the pregnancy. The criminalization of abortion coincided with the rise in power of doctors and the medicalization of reproduction (Rankin, 2022).

With the criminalization of abortion came an increase in maternal deaths. In the 1930s, the height of the Great Depression, one in five maternal deaths was attributed to abortion (Rankin, 2022). But the advent of penicillin greatly reduced the risk of septicemia and death. By 1968 the National Center for Health Statistics reported 168 abortion-related deaths (Prager, 2021). In addition to the growing safety concerns, an outbreak of rubella, and the devastating effects of the tranquilizer thalidomide on a developing fetus, made people rethink their stance on abortion and whether a mother should be carrying to term a child with severe birth defects (Prager, 2021).

Many individual doctors were sympathetic to the plight of their female patients, but terrified of the consequences for their own careers. No doubt because the American Medical Association (AMA) was not supportive, and had for decades crusaded against abortion (Prager, 2021). Making abortion illegal, except when a mother’s life was at risk, empowered the AMA, as only doctors were allowed to determine whether an abortion was medically necessary. However, by the late 1960s, some states were allowing abortion in the case of rape or incest, or if the fetus had severe birth defects. They were also starting to expand the definition of “mother’s health” to include her mental health; something the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with in the 1971 United States v. Vuitch ruling (American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU, 2010). By then, the AMA had also changed its stance and was asking doctors to abide by the changing state rules (Prager, 2021).

Roe v. Wade (1973)

Seventeen abortion challenges were making their way to the Supreme Court when the Vuitch ruling was handed-down, including the landmark Roe v. Wade (ACLU, 2010). Roe v. Wade was a constitutional challenge to a Texas law that made it illegal to have an abortion in all but situations where the mother’s life was at risk (Brennan Center for Justice, 2022). The court used the 14th Amendment and its implied right to privacy, just had it had years earlier in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) when it struck down the Barnum Act; a law in the State of Connecticut since 1879 outlawing contraceptives or the distribution of information about contraceptives (Brennan Center for Justice, 2022). Sarah Weddington presented the challenge to Texas abortion laws, and argued that “meaningful liberty must include the right to terminate a pregnancy” (Brennan Center for Justice, 2022, para. 23). In a decision written by Justice Blackmun, seven of the nine justices agreed that the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment protects people against states violating the right to privacy, and a woman’s choice to have an abortion falls within that right (Oyze, 2022.). However, the justices did recognize the right of a state to regulate access as the pregnancy progressed. After the fetus had entered the third trimester, a state could ban abortion, but even then a woman could have access to an abortion if it was necessary to protect the woman’s health or life (ACLU, 2010). Forty-six states had to change their laws after the Supreme court ruling (Brennan Center for Justice, 2022). Since that time states, citizens, and the medical community have fought over what limits governments could place on access to abortion.

Planned Parenthood v. Danforth (1976)

Planned Parenthood v. Danforth (1976) challenged a provision in the State of Missouri’s law which required women who wished to terminate a pregnancy in the first trimester needed the written consent of her spouse if she was married. The Supreme Court ruled that this law was unconstitutional as it gave the spouse vetoing power, which even the state itself was prohibited from having during the first trimester of pregnancy (Legal Information Institute, 2022).

Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992)

In 1992 the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional right to abortion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. However, this case led the court to overturn the trimester framework set in Roe v. Wade, and instituted a viability framework ruling that prohibitions on access to an abortion could be made once a fetus reaches viability (Planned Parenthood, 2022). Under Roe the state could not restrict access to an abortion in the first trimester. In the second trimester, some restrictions were allowed, but abortions could be performed in the best interest of the mother. In the third trimester, the state could outlaw abortions in the best interest of the fetus, unless it compromised the woman’s health (Shivaram, 2022). With the Casey ruling the trimester system was scrapped, and states could use age of viability as the determining factor in restricting abortions.

In addition, it also allowed restrictions as long as there was not an “undue burden” (Shivaram, 2022). This would open the door to states restricting access to abortion. What constitutes a burden is a very grey area and allowed states to add waiting periods, parental notification if a minor, counseling, and additional hospital and doctor restrictions. For a woman who had easy access to clinics and hospitals, and the financial and transportation resources, very few added requirements by a state would be an undue burden, but for others this would be an obstacle to access.

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022)

The Supreme Court in a 6-3 decision upheld a Mississippi Law (2018) that banned abortion at 15 weeks, which is before the age of viability, and in a 5-4 decision to overturn both Roe and Casey. If Roe and Casey were wrongly decided, as Dobbs argued and the majority of the Supreme Court agreed, then the age of viability was no longer a limiting factor for State laws. Here is what the Syllabus of the Supreme Court ruling says in regard to Roe and Casey.

Guided by the history and tradition that map the essential components of the Nation’s concept of ordered liberty, the Court finds the Fourteenth Amendment clearly does not protect the right to an abortion. Until the latter part of the 20th century, there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. No state constitutional provision had recognized such a right. Until a few years before Roe, no federal or state court had recognized such a right. Nor had any scholarly treatise. Indeed, abortion had long been a crime in every single State. At common law, abortion was criminal in at least some stages of pregnancy and was regarded as unlawful and could have very serious consequences at all stages. American law followed the common law until a wave of statutory restrictions in the 1800s expanded criminal liability for abortions. By the time the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, three-quarters of the States had made abortion a crime at any stage of pregnancy. This consensus endured until the day Roe was decided. Roe either ignored or misstated this history, and Casey declined to reconsider Roe’s faulty historical analysis (Syllabus for Dobbs v. Jackson, 2022, p. 3).

…Roe was also egregiously wrong and on a collision course with the Constitution from the day it was decided. Casey perpetuated its errors, calling both sides of the national controversy to resolve their debate, but in doing so, Casey necessarily declared a winning side. Those on the losing side—those who sought to advance the State’s interest in fetal life—could no longer seek to persuade their elected representatives to adopt policies consistent with their views. The Court short-circuited the democratic process by closing it to the large number of Americans who disagreed with Roe (Syllabus for Dobbs v. Jackson, 2022, p.5).

Post Roe v Wade: President Biden’s Reactions

President Joe Biden called it “a sad day for the court and for the country” as this was the first time that the Supreme Court had revoked a constitutional right (Bustillo, 2022, para. 3). He asked the Department of Health and Human Services to make sure that abortion and contraceptive medications are available, and that his administration will protect the right to cross state lines to have an abortion. He also asked women to “turn out in record numbers to reclaim the rights that have been taken from them by the court” (Parker et al., 2022, para. 13).

Trigger Bans

Many states had in place laws that were triggered to go into effect when Roe v. Wade was overturned. These states are Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin (Jefferies et al., 2022). The Michigan and Louisiana laws are currently tied up in litigation.

The Kansas Vote and other State Initiatives in the 2022 Mid-term Elections

On August 2, 2022, in the first test after the supreme court overturned Roe v. Wade, voters in the state of Kansas rejected a ballot measure to remove abortion rights protections from the state constitution. The measure lost by 18%, with the results standing even after a recount (Associated Press, 2022). Voters in four states, California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Vermont, had the opportunity to decide whether a woman’s right to an abortion will be part of the state constitution (Long, 2022). Voters in Montana voted on issues related to abortion but it did not address the state constitution.

The Michigan question almost did not make the ballot. Antiabortion group Citizens to Support MI Women and Children raised objections to a proposed question about protecting abortion rights in the state’s constitution because of typographical and formatting errors (“DECISIONSABOUTALLMATTERSRELATINGTOPREGNANCY”). The Michigan’s State Board of Canvassers, which determines what is be placed on the state’s election ballots, was deadlocked when the decision to reject the proposed question split along party lines. The Michigan Supreme Court ordered that the question be placed on the November ballot, and chastised the behavior of the two Republican members of the State Board for using a technical error that did not hamper the intent or meaning of the question to block its inclusion on the ballot for political reasons (Bellware, 2022, September 8).

In all states where abortion rights were on the chopping block in the 2022 mid-term elections the voters in those states chose to protect those rights, signaling a shift in American attitudes about a woman’s right to have access to abortion. The results of the 2024 election were a little more mixed.

State Initiatives in the 2024 Elections

During the 2024 election, voters in 11 states were asked to make decisions on abortion rights (Brewer, 2024). Arizona, Colorado, Maryland, Missouri, Montana, and Nevada passed measures to protect access to abortion, while those in Florida and South Dakota did not garner enough votes to protect access. In Illinois, voters approved a non-binding question on whether health insurance should cover abortion costs. Additionally, voters in New York passed the Equal Protection Under Law Amendment, which prohibits discrimination based on reproductive care decisions, including abortion.

In the next module we will consider how gender impacts both mental health, and its role in both seeking and receiving treatment.