Main Body

Module 1 What is the Psychology of Gender?

What are little boys made of?

Snips and snails

And puppy-dogs’ tails

That’s what little boys are made of

What are little girls made of?

Sugar and spice

And everything nice

That’s what little girls are made of

Sex and gender are both central to our lives, but they are often a source of controversy. Reflect on how dramatically our attitudes and beliefs regarding sex and gender have changed in the last few years. In 2016, a woman was on the final ballot representing a major political party for president. In 2017, the Boy Scouts of America opened their organization to transgender children. In the 2018 mid-term election, more women were elected to serve in congress than in any prior election in American history. In the 2020 election, a woman of color was elected as Vice President, and on January 20, 2021 Kamala Harris took the oath of office. The concepts of sex and gender shape our identities, our opportunities, and our relationships.

Sex and gender are both central to our lives, but they are often a source of controversy. Reflect on how dramatically our attitudes and beliefs regarding sex and gender have changed in the last few years. In 2016, a woman was on the final ballot representing a major political party for president. In 2017, the Boy Scouts of America opened their organization to transgender children. In the 2018 mid-term election, more women were elected to serve in congress than in any prior election in American history. In the 2020 election, a woman of color was elected as Vice President, and on January 20, 2021 Kamala Harris took the oath of office. The concepts of sex and gender shape our identities, our opportunities, and our relationships.

The Central Concepts

Sex is used to categorize people based on genetic, chromosomal, and anatomical differences as male, female, or intersex, often thought of as biologically determined. Gender refers to the social meanings ascribed to people who belong to a particular sex. The reality of these two terms is more complicated. While traditionally, sex has been thought of as untainted by societal influences, and gender as socially constructed, the argument can be made that both terms are socially constructed. As you will see in a later module, there are several biological markers for femaleness and maleness, but most cultures use only one of those markers to assign babies to a particular sex, the external genitalia. However, nature lies. There may be a mismatch between internal and external reproductive systems, or between chromosomes and external genitalia. The sex and gender binaries are a social system that consists of two non-overlapping, opposing groups. Male and female, and masculine and feminine are used in most, but not all cultures, as they simplify interactions between societal members, aid in organizing division of labor, and help maintain social institutions (Bosson et al., 2019). However, our understanding of research into sex and gender has moved beyond the constraints of a binary system. Both variables currently include a range of categories that better fit to an individual’s own self-identification.

Gender Identity refers to a person’s psychological sense of being male, female, both, or neither. Categories of gender identity include:

- Cisgender or cis refers to individuals who identify with the gender assigned to them at birth. Some people prefer the term non-trans.

- Transgender generally refers to individuals who identify as a gender not assigned to them at birth. A gender transition is based on one’s identity and social expressions. Some individuals who transition do not experience a change in their gender identity since they have always identified in the way that they do. The term is used as an adjective (i.e., “a transgender woman,” not “a transgender”), however some individuals describe themselves by using transgender as a noun. The term transgendered is not preferred because it undermines self-definition.

- Trans is an abbreviated term, and individuals appear to use it self-referentially more often than transgender (Tompkins, 2014).

- Non-binary and genderqueer refer to gender identities beyond binary identifications of man or woman. The term genderqueer became popularized within the queer and trans communities in the 1990s and 2000s, and the term non-binary became popularized in the 2010s (Roxie, 2011).

- Agender, meaning “without gender,” can describe people who do not have a gender identity, while others identify as non-binary or gender neutral, have an undefinable identity, or feel indifferent about gender (Brooks, 2014).

- Genderfluid which highlights that people can experience shifts between gender identities.

Additional gender identity terms exist; these are just a few basic and commonly used terms. Again, the emphasis of these terms is on viewing individuals as they view themselves and using self-designated names and pronouns.

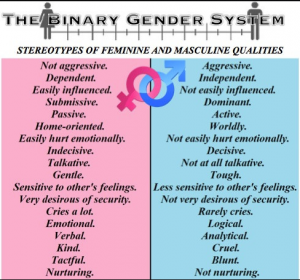

Similar to the sex-binary, the gender-binary assumes that individuals are either masculine or feminine. However, gender identity is currently viewed to be thought of as being on a continuum. Masculinity refers to the attributes most commonly associated with men in a culture. Femininity refers to the attributes a culture most commonly associates with women. Androgyny refers to possessing both stereotypical masculine and feminine traits. As some stereotypical masculine traits, such as being analytical or independent, and some stereotypical feminine traits, such as being nurturing or affectionate, predict more positive outcomes for people, researchers have wanted to know if being more androgynous is psychologically healthier. Scott et al. (2015) found in their study of over 4,800 young people in the United States, that androgyny was associated with more positive outcomes for White and Latinx girls, but not among boys. Boys who fit the more traditional masculine gender role predicted a better quality of life.

Similar to the sex-binary, the gender-binary assumes that individuals are either masculine or feminine. However, gender identity is currently viewed to be thought of as being on a continuum. Masculinity refers to the attributes most commonly associated with men in a culture. Femininity refers to the attributes a culture most commonly associates with women. Androgyny refers to possessing both stereotypical masculine and feminine traits. As some stereotypical masculine traits, such as being analytical or independent, and some stereotypical feminine traits, such as being nurturing or affectionate, predict more positive outcomes for people, researchers have wanted to know if being more androgynous is psychologically healthier. Scott et al. (2015) found in their study of over 4,800 young people in the United States, that androgyny was associated with more positive outcomes for White and Latinx girls, but not among boys. Boys who fit the more traditional masculine gender role predicted a better quality of life.

A Brief History of the Women’s Movement in the U.S.

Feminism, also known as the feminist or women’s movement, encompasses many social movements that emphasize improving women’s lives and rectifying gender inequality in society (Young, 1997). Overtime the focus has shifted as gains were made, or circumstances changed. The issues have ranged from women’s right to vote, hold property, receive equal pay and employment opportunity, reproductive rights, domestic violence, sexual harassment, and sexual violence and exploitation. Given the diversity of issues and voices that have been added to the movement it is described as having four waves.

First Wave

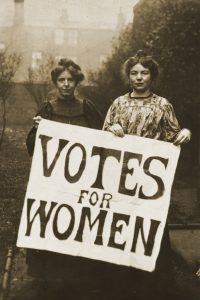

What has come to be called the “first wave” of the feminist movement in the Unites States began in the mid-19th century and lasted to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which gave women the right to vote. White middle-class suffragists, such as Elizabeth Clay Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, focused on women’s suffrage, that is, the right to vote. Suffragists also worked on striking down coverture laws, which stated upon marriage a woman could no longer own property or enter into contract in her own name, and a woman’s right to education and employment (Kang et al., 2017).

Demanding women’s equality, the abolition of coverture, and access to employment and education were quite radical demands at the time. These demands confronted the ideology of the cult of true womanhood, summarized in four key tenets: piety, purity, submission and domesticity. These held that women were rightfully and naturally located in the private sphere of the household and not fit for public, political participation, or labor in the waged economy (Kang et al., 2017). However, this emphasis on confronting the ideology of the cult of true womanhood was shaped by the white middle-class standpoint of the leaders of the movement. This leadership shaped the priorities of the movement, often excluding the concerns and participation of working-class women and women of color.

Second Wave

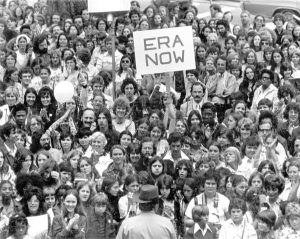

The “second wave” of feminism, from 1920-1980, focused generally on fighting patriarchal structures of power, and specifically on combating occupational sex segregation in employment and fighting for reproductive rights for women (Kang et al., 2017). The Civil Rights Act of 1964, a major legal victory for the civil rights movement, not only prohibited employment discrimination based on race, but Title VII of the Act also prohibited sex discrimination. When the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency created to enforce Title VII, largely ignored women’s complaints of employment discrimination, 15 women and one man organized to form the National Organization of Women (NOW). NOW focused its attention and organizing on the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), fighting sex discrimination in education, and defending Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court decision of 1973 that struck down state laws that prohibited abortion within the first three months of pregnancy.

White women were not the only women spearheading feminist movements. As historian Thompson (2002) argues, in the mid and late 1960s, Latinx women, African American women, and Asian American women were developing multiracial feminist organizations that would become important players within the U.S. second wave feminist movement. However, during this era Black women writers and activists such as Alice Walker, bell hooks, and Patricia Hill Collins developed Black feminist thought as a critique of the ways in which some second wave feminists still ignored racism and class oppression and how they uniquely impact women and men of color and working-class people. bell hooks (1984) argued that feminism cannot just be a fight to make women equal with men, because such a fight does not acknowledge that all men are not equal in a capitalist, racist, and homophobic society. Sexism cannot be separated from racism, classism and homophobia, and that these systems of domination overlap and reinforce each other. These critiques led to the third wave of feminism.

Third Wave

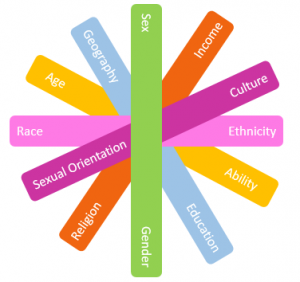

“Third wave” feminism came directly out of the experiences of feminists in the late 20th century who grew up in a world that supposedly did not need social movements because “equal rights” for racial minorities, sexual minorities, and women had been guaranteed by law in many countries (Kang et al., 2017). However, the gap between law and reality, between the abstract proclamations of states and concrete lived experience, revealed the necessity of both old and new forms of activism. Moreover, third-wave feminism criticized second wave feminism’s focus on the universality of women’s experiences. Emerging from the criticism of Black feminists, third wave feminism emphasized the concept of intersectionality. Intersectionality views race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity as mutually constitutive; that is, people experience these multiple aspects of identity simultaneously and the meanings of different aspects of identity are shaped by one another.

Fourth Wave

Currently we are in the “fourth wave”, and fourth wavers are not just the reincarnation of their second and third wave grandmothers and mothers. There is a greater emphasis on intersectionality and the diversity of women (Ramptom, 2015). It has borrowed from third wave feminist and understanding that feminism is part of a larger context of oppression, along with ageism, racism, ableism, classism, and those of different sexual orientations. But fourth wave feminism also rejects the gender binary and focuses on transgender issues. As Ramptom writes “feminism no longer just refers to the struggles of women; it is a clarion call for gender equity” (p.7). Gender equality was the focus of much of the women’s movement. Gender equality refers to not discriminating on the basis of a person’s gender when it comes to access to services, the allocation of resources, or opportunities (McRaney et al. 2021). Gender equity refers to there being fairness and justice in the distribution of resources and responsibilities on the basis of gender (McRaney, et al., 2021).

Fourth wavers have also capitalized on technological advances to promote their campaigns and raise public awareness to gain support (National Women’s History Museum, 2021). Hashtags such as #YesAllWomen, #BringBackOurGirls, and #MeToo have promoted the experiences that women have with violence and harassment. Social media has also galvanized marches in various cities and in the nations capital. Fourth wavers are now more global in their message and in their membership (National Women’s History Museum, 2021).

Feminist Theories

Feminist theory grew out of the feminist/women’s movement that began around 1830 in the United States and Europe. Feminist theory actually consists of many different perspectives, as no single person or perspective is the main authority. Although focusing on different aspects of the female experience, all feminist theories advocate for eliminating gender inequalities and oppression. According to Else-Quest and Hyde (2018), the following are the major points of feminist theories:

- Gender is socially constructed. Feminist theories emphasize that individual cultures and societal influences create and maintain gender roles that perpetuate gender inequality, male domination, and female subjugation. Due to women’s perceived lower status, they are discriminated against in diverse ways, including academically, politically, economically, and interpersonally.

- Men exercise power and control over women. Because men have seized power, they use that power in interpersonal relationships, including rape and domestic violence, in politics by passing laws that harm women, and economically by supporting different pay scales for jobs reflecting traditional gender roles. Men’s sense of entitlement and privilege allow them to exert power without fear of consequences.

- Women’s problems are due to external factors rather than internal factors. Mental health disorders in women, and being the victims of violence, are often viewed as being due to internal/personal reasons. This includes that women are naturally more emotional, and therefore more likely to suffer from a mental health disorder, or they dressed provocatively and therefore were responsible for being raped. Instead, feminist theories see external factors, such as sexism, discrimination, male aggression, and female inequality as the reasons for problems faced by women.

- Consciousness raising is an important aspect of all theories. Consciousness raising involves women first sharing their experiences and reflecting on them. Next, they engage in an analysis of their feelings and experiences. Lastly, they develop action plans to address any negative consequences from their experiences. This could include political or social actions, as well as making changes in interpersonal relationships.

Others have noted that feminist theory, as a collective, is a theoretical position which examines the world through the lens of gender but has a focus that is varied and wide-ranging (Evans, 2014). Thus, feminism is not afraid to engage in issues outside of gender, and understands that changes in the everyday circumstances of people’s lives, such as technology and even the outward trappings of society, does not inevitably bring with it changes in power, privilege, and authority. Many view that it is the role of feminist theory to challenge much of our social knowledge, which has always been supported by, and maintained, the authority of men.

According to Else-Quest and Hyde (2018), Renzetti et al. (2012), and Kang et al., (2017) there are several major types of feminist theory and they include:

Liberal Feminism holds that women and men are equal and should have the same opportunities. Liberal feminists tend to work within the current system for change to ensure that women have full access to legal, educational and career opportunities. The National Organization for Women (NOW) reflects liberal feminism, and this organization worked to pass the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) which states, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex” (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018, p. 6). The ERA was passed in the House of Representatives and Senate in 1972, and finally has been ratified by all the 38 states needed to pass it, with Illinois becoming the 37th state May 30, 2018, and Virginia becoming the 38th on January 27, 2020. However, Congress set a 1982 deadline to ratify ERA, so the gesture by these states may be more symbolic. Moreover, several states (Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Tennessee) have voted to rescind their earlier ratification. However, states can only ratify an amendment, according to Article V of the constitution; they do not have the power to rescind a ratification (Equal Rights Amendment.org, 2018). This means the question of ERA is still in legal limbo.

Cultural Feminism, unlike liberal feminism, believes that women have special and unique qualities that have been devalued by a patriarchal society. The emphasis of cultural feminism is that these qualities, including nurturing, connectedness, and intuition, need to be elevated in society.

Radical Feminism opposes current political and social organizations because they are tied to patriarchy and the domination of women by men. Radical-cultural feminism argues that feminine values, such as interdependence, are preferable to masculine values, such as autonomy and dominance, and therefore men should strive to be more feminine. In contrast, Radical-libertarian feminism focuses on how femininity limits women and instead advocates for female androgyny. Because changing the current patriarchal society will be a difficult process, some radical feminists advocate for separate societies where women can work together free from men.

Women-of-Color Feminism promotes an intersectional model of feminism that emphasizes the unique situation of women of color being in multiple marginalized groups. The diversity of women’s experiences is considered more important than universal female experiences.

Marxist/Socialist Feminism concludes that the oppression of women is an example of class oppression based on a capitalist system. Women’s lower wages, for example, benefit corporate profits and the current capitalist economic system. Marxist/Socialist feminists argue that there should be no such category as “women’s work”, and they believe that women’s status will only improve with a major reform of American society.

Postmodern Feminism views sex and gender as socially determined scripts. They do not support a dualistic view of gender, heteronormativity, or biological determinism Instead, postmodern feminists see gender and sexuality as more fluid. Postmodern feminism is part of the fourth wave of feminism that is evident today.

Ecofeminism is concerned with environmentalism, and some of the most powerful leaders in the environmental movement have been women. Ecofeminism emerged in the 1970s and supports an earth-based spirituality movement that incorporates goddess imagery, female reproduction, healing, and a belief that all living beings are equal and should be respected. Ecofeminism also incorporates a wide range of intersectionality, including women of color, poor women, women with disabilities, and those who are trans and non-gender conforming. Historically, marginalized groups have experienced the brunt of extreme weather, unlawful working conditions, and exposure to toxins and pollution. Ecofeminism looks at these environmental issues through a social justice lens, critically analyzes their effects, and supports the needs of affected, marginalized people (Villalobos, 2017). Additionally, ecofeminism analyzes how western economic models have exploited and discriminated against those in economically underdeveloped societies

Ecofeminism also rejects a patriarchal society that is believed to harm both women and nature. The same societal structures (sexism, racism, classism) that oppress women and minorities, are also believed to be exploiting the environment. Applying ecofeminism in practice incorporates the blending of biocentricism, which endorses inherent value to all living things, and anthropocentricism, which focuses on humans being the most important entity in the universe. Ecofeminists support the needs of both nature and humans, and they encourage those with privilege to use it for good by advocating with, and on behalf of, others.

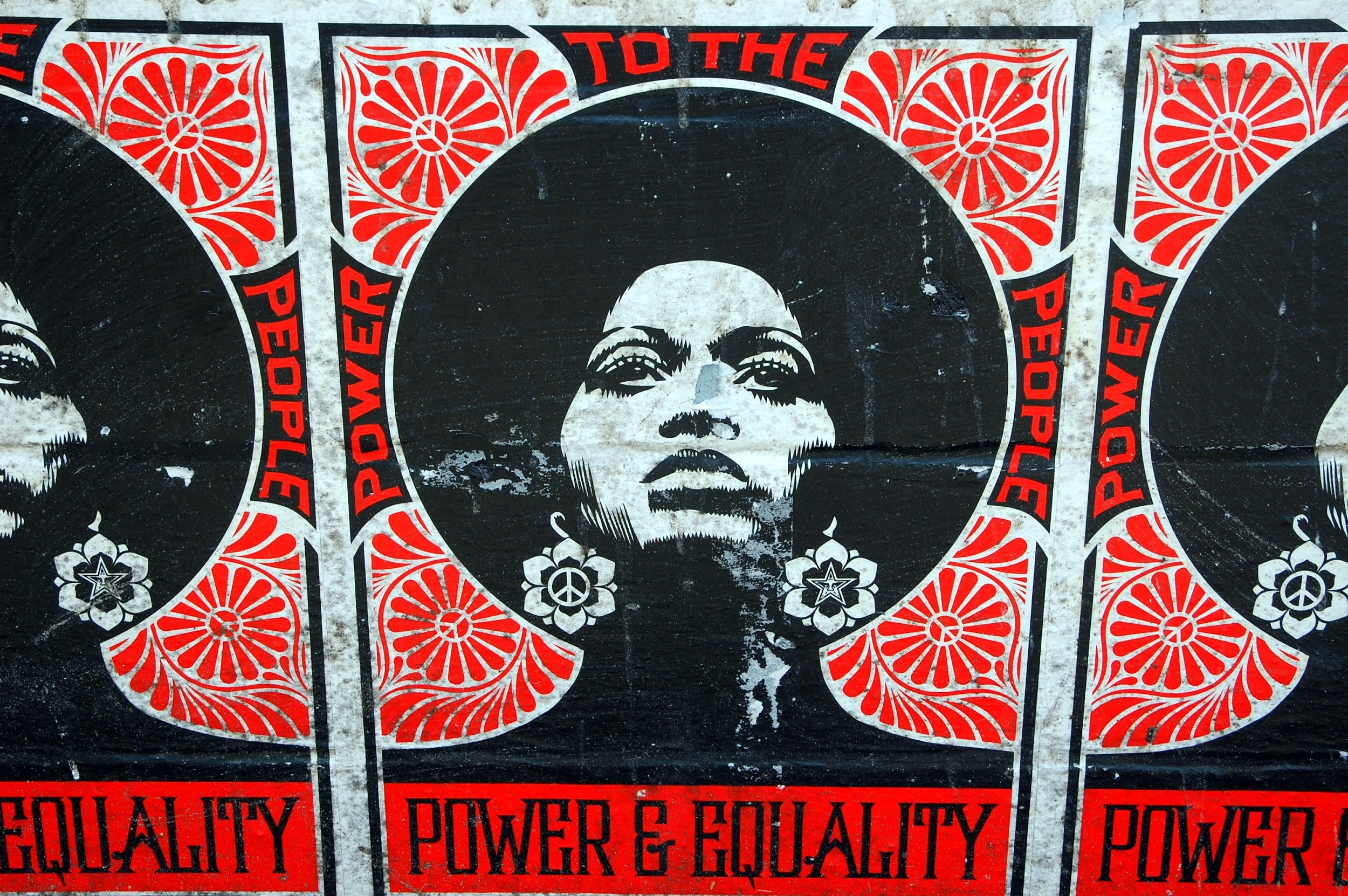

Black Feminism focuses on the interconnections among race, gender, class, sexual orientation and geography, as well as how they affect the wellbeing of Black women, Black families, and Black communities (Few, 2007). Even though they possess varying levels of privilege, black women still experience oppression unique to their identity. Specifically, Black men and women both experience racism and classism, but sexism exists in both personal and public settings. Although all women are affected by sexism, the relationship between Black and White women is influenced historically by enslavement and the emergence of the White women’s liberation movement. White feminist groups focused on White, middle class experiences that did not address the issues of poor and working-class Black women or address racism. Black feminists detailed how women experienced sexism differently based on their racial identity. Few (2007) stated: “Black and White womanhood differ and traditional housewife models of womanhood are not applicable to most Black women. In addition, historically, Black women have been more likely to be heads of household than White women and their labor contribution to the marketplace has always exceeded that of White women,” (p. 308).

Black Feminism focuses on the interconnections among race, gender, class, sexual orientation and geography, as well as how they affect the wellbeing of Black women, Black families, and Black communities (Few, 2007). Even though they possess varying levels of privilege, black women still experience oppression unique to their identity. Specifically, Black men and women both experience racism and classism, but sexism exists in both personal and public settings. Although all women are affected by sexism, the relationship between Black and White women is influenced historically by enslavement and the emergence of the White women’s liberation movement. White feminist groups focused on White, middle class experiences that did not address the issues of poor and working-class Black women or address racism. Black feminists detailed how women experienced sexism differently based on their racial identity. Few (2007) stated: “Black and White womanhood differ and traditional housewife models of womanhood are not applicable to most Black women. In addition, historically, Black women have been more likely to be heads of household than White women and their labor contribution to the marketplace has always exceeded that of White women,” (p. 308).

Because the women’s liberation movement was seen as a white movement, and the black liberation movement was largely seen as a black male movement, Black feminist activists founded the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO) in 1973. The NBFO was the first explicitly Black feminist organization in the United States (Few, 2007). The NBFO resulted not only from Black women’s frustration with racism in the women’s movement, but also a desire to raise the consciousness and connections of all Black women. Black feminists focused on defining themselves and rejecting internalized oppression as a way of fighting sexism and racism. Current Black feminists look to popular culture (e.g., hip-hop) and art (e.g., performance, photography, dance) to analyze black women’s lives, activism, and the development of Black female identity.

A Brief History of Men’s Movements in the U.S.

In the early 1970s informal discussion groups of men at colleges and universities started to question how male gender role stereotypes and norms were harmful to men (Renzetti et al., 2012). By the end of the decade, two camps had formed among Men’s Movement groups and writers. The male-identified camp is highlighted by writers like Goldberg (1976) who wrote “The Hazards of Being Male”. However, the subtitle of his book, “Surviving the Myth of Male Privilege,” suggests that while he recognized the toxicity of the masculine gender role for men, he did not believe that the same role was the main reason why women were suffering under the patriarchal system. To him, and other members of this camp, patriarchy is a myth (Edley, 2017). It is men who are the subordinated sex; women are more advantaged and protected. It is women who seduce men then claim rape, women who make false claims to the courts about spousal abuse, and child abuse, to gain sole custody of their children, but it is men who are expected to pay to support the family they are no longer allowed to see (Renzetti et al., 2012). The male-identified camp is antifeminist, and includes a number of faith based men’s groups, such as the Promise Keepers and the Nation of Islam, along with groups helping men find their inner wild man.

In contrast, the female-identified camp is explicitly pro-feminist, and examines both men’s relationships with women, and with other men. These groups recognize that there needs to be social changes to remove the gender inequalities. They also recognize that this domination and subordination is not just along gender lines, but also along racial, ethnic, social class, and sexual orientation. Groups such as the National Organization of Men Against Sexism (NOMAS) advocate “a perspective that is pro-feminist, gay affirmative, anti-racist, dedicated to enhancing men’s lives, and committed to justice on a broad range of social issues including class, race, age, religion, and physical abilities” (NOMAS, 2017, Principles, para. 1). The Good Men Project started as research for a book by Matlack and colleagues in 2009, The Good Men Project: Real Stories from the Front Lines of Modern Manhood (Houghton et al., 2009). Matlack was interested in telling the stories of the defining moment in men’s lives. Matlack said that there was a point in every man’s life when he looks in the mirror and says “I thought I knew what it meant to be a man. I thought I new what it meant to be good. And I realize that I don’t know either” (The Good Men Project, n.d., About us, para. 1). The Good Men Project tackles issues relevant to men’s lives, from fatherhood, sex, ethics, aging, gender, sports, pornography, and politics. In their view men are neither “mindless, sex-obsessed buffoons nor the stoic automatons our culture makes them out to be” (The Good Men Project, n.d. About us, para. 4). Both groups challenge the traditional gender role for men. While NOMAS directly confronts how that role negatively impacts the lives of men and women, the Good Men Project helps men navigate the changing social landscape of sex and gender.

Masculinity Theories

Many of the early psychological theorists and researchers in psychology, as well as their research participants were men, and typically white males of a higher socioeconomic status (Pleck, 2017). So it may not seem surprising that psychology viewed men’s reactions and development as the human norm and basis for psychological theories. However, given that this norm was also embedded within a particular social class, ethnic group, and sexual orientation, many men did not fit the profile for this norm. This spawned renewed interest in studying the lives of men, as men, not as the stand-in for all humans.

Over 80 years ago, the trait of masculinity-femininity (m-f) was first introduced to psychology by Terman and Miles (1936). Many studies in the 1940s focused exclusively on how males scored on measures of this trait. As many fathers had been absent in World War II, psychologists wanted to know how this impacted the gender role development of boys. As women took to the factories during the war, researchers also looked at how having a mother who worked outside of the home impacted the gender role development of boys.

The progression of views regarding masculinity and femininity began as conceptualizing the two on opposite sides of a continuum (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018). This one-dimensional, bipolar continuum was supported by survey questions indicating that men responded “yes” to questions related to stereotypical masculine identities, while women responded “yes” to questions that were more stereotypical feminine.

Are masculinity and femininity really opposites of each other or can individuals demonstrate both characteristics? Of course, individuals can demonstrate androgyny, as they exhibit both masculine and feminine behaviors. The concept of androgyny is based on a two-dimensional model of masculinity-femininity instead of the one-dimensional model previously illustrated. With this representation, a person can have a high score on both femininity and masculinity and would fall in the upper right quadrant of this model.

According to Pleck (2017), research on male gender identity, using trait m-f measures, grew to link it to a wide range of phenomena: Male psychological adjustment, male homosexuality, male transsexuality, male delinquency and hyper-masculinity, male initiation rites in non-Western cultures, boys’ difficulties in the schools, and racial/ethnic and social class differences among males (Pleck, 2017, p. xii).

The research on trait m-f in men was embedded in what has come to be called the gender role identity paradigm, and this paradigm dominated ideas, theories, and research on development, personality, and clinical psychology during this time. Gender role identity paradigm (GRIP) made the assumption that successful personality development hinged upon the formation of a gender role that was consistent with the person’s biological sex (Levant & Powell, 2017). GRIP was based on Freudian psychoanalytic theory. The failure of men to achieve a masculine identity was believed to be the root of homosexuality, negativity toward women, or hyper-masculinity to compensate for this failure. This view emerged from an essentialist view about sex and gender. It assumed that “there is a clear masculine “essence” that is historically invariant, that is, that biological sex determined gender” (Levant & Powell, 2017, p. 16-17).

Gender Role Strain Paradigm (GRSP): Pleck (1981) in his book, The Myth of Masculinity, introduced the concept of sex-role strain. Pleck (1995) later referred to this idea as the gender role strain paradigm (GRSP). Gender role strain refers to the pressure to live up to gender role ideals, and often results in psychological distress. Pleck drew from feminist and constructionist ideologies and applied them to masculinity and the lives of men (Levant & Powell, 2017). At the heart of this paradigm is the notion that traditional gender roles serve to maintain and protect patriarchal social order. Rewards are bestowed on those who conform to sex-typed behavior, while those who challenge them are ignored or punished. Overtime, these socially constructed gender-roles are seen as the norm, natural, and expected.

According to the GRSP (Levant & Powell, 2017):

- Gender roles are defined and constructed by the stereotypes and norms of the culture

- Gender roles are contradictory and inconsistent

- Violation of gender roles leads to social condemnation, and negative psychological consequences

- Violating gender roles have more negative consequences for men than for women

- Most people do not always act consistent with the gender roles

- Certain gender role traits are dysfunctional

- Each gender experiences gender role strain in the workplace and relationships

- Historical changes cause gender role strain

From this perspective, the traditional masculine gender role is impossible to achieve and is inherently harmful, leading men to experience gender role strain. This strain may lead men to experience pressure to conform to the male gender role, and in an effort to avoid social rejection and to gain the social reward of being considered a “man”, over time men will adopt a more rigid gender role (Isacco & Wade, 2017).

Pleck identified three sources of gender role strain: Discrepancy strain, dysfunction strain, and trauma strain.

Discrepancy strain occurs when a person fails to live up to the social standards for the gender role. As gender role norms are sometimes contradictory and inconsistent, men will invariably violate the norms. Pleck proposed that this discrepancy would lead to lower-self-esteem and other negative psychological issues when men fail to live up to the standards of the masculine gender role.

Dysfunction strain suggests that some of the gender role norms are inherently psychologically and physically harmful (Levant & Powel, 2017). Consider the main components of the traditional masculine gender role.

- Men should not be feminine

- Men should not show weakness

- Men should always strive for respect and success

- Men should always seek adventure, and never shy away from risk

Within each of these components are traits that can have negative side-effects on both men and those around them. This “dark side of masculinity” (Brooks & Silverstein, 1995) involves various types of violence, relationship failures, and socially irresponsible actions. Men who fail to achieve the ideals of manhood frequently have their status as a “real” man questioned. This is the precarious manhood hypothesis, a tenuous social status that is difficult to attain, but easy to lose (Vandello & Bosson, 2013). Men’s status as men requires validation, as a result men are constantly being asked to prove their manhood. This is something that women rarely encounter. Moreover, men who lose certain social achievements, such as employment, are more likely to expect that others will see them as less of a man.

Trauma strain refers to the notion that the socialization of males to achieve the traditional masculine gender-role is traumatic (Levant & Powel, 2017). In some societies males may have to go through some rite of passage to achieve manhood. This may involve taking them away from their mothers at a young age, or facing danger or withstanding pain to prove they are a man. Even in societies that do not have a specific rite of passage, males are expected to shield their emotions, to not flinch in the face of danger, and to never show weakness.

Pleck (1995) later created the notion of masculine ideology. Masculine ideology is defined as “the individual’s endorsement and internalization of cultural belief systems about masculinity and the male gender” (p. 19). Masculinity, like femininity, is tied to the cultural and historical context. Thus, there may be many masculinities. However, in many cultures there is often a dominant set of expectations that serve as the foundation of cultural beliefs about what it means to be a man. This has often been referred to as hegemonic masculinity or traditional masculinity ideology (Rowbottom et al., 2012). Pleck’s concept of masculine ideology led others to consider how the extent to which men hold such beliefs affects their self-worth and is dependent on the reference group men are using.

Masculinity Contingency: This concept refers to the extent to which a man’s sense of self-worth is related to his sense of masculinity (Isacco & Wade, 2017). This concept hypothesizes that a man who is high in masculinity contingency would experience more fluctuations to self-worth because it would be contingent on his masculinity being validated by others. Masculinity contingency involves both contingency threat, which refers to the extent to which a lack of masculinity threatens a man’s self-worth, and contingency boost, where confirmation of masculinity elevates a man’s self-worth.

Male Reference Group Identity Dependence: This theory was proposed by Wade (1998) and is based on Erikson’s ego identity theory and Sherif’s reference group theory (Isacco & Wade, 2017). Ego identity is the self-image that we form in adolescence and young adulthood that is the integration of our ideas about who we are and who we want to be (Schultz & Schultz, 1994). A reference group is the group we use for comparison. It provides us with the norms, expectations, beliefs, and customs. The “extent to which a male is dependent on a male reference group for his gender role self-concept” defines male reference group identity dependence (Isacco & Wade, 2017, p.144).

According to this theory there are three levels of psychological relatedness: psychological relatedness to all males, to just some males, or no sense of connection to other males (Isacco & Wade, 2017). The theory hypothesizes that when males feel relatedness to just some groups of men their gender role self-concept is likely to conform to that group’s norms, and such men will hold more rigid views about what is appropriate, expected, or desired behavior in men. When the connection is to all males, since there is no single reference group, the gender self-concept is likely to be more self-defined, and such men’s gender-related attitudes will be more flexible and autonomous. If there is no male reference group there may be confusion with regard to gender-related norms and attitudes, and the male may experience feelings of alienation and insecurity.

Gay Rights and Transgender Movements

According to Morris (2016), there is historical evidence of same-sex relationships in every documented culture. Further, there is evidence of individuals living as a gender different than the one assigned at birth. Females lived as males in order to be part of the military, attend schooling and work, while males also exhibited transgender behavior, especially in the performance arts. Despite the presence of LGBTQ individuals in diverse cultures, European and Christian colonizers rejected behaviors that deviated from their views of masculine and feminine roles and enforced sodomy laws, which defined certain sexual acts as crimes. Consequently, through much of history, LGBTQ individuals were stigmatized, arrested and labeled deviant.

According to Morris (2016), there is historical evidence of same-sex relationships in every documented culture. Further, there is evidence of individuals living as a gender different than the one assigned at birth. Females lived as males in order to be part of the military, attend schooling and work, while males also exhibited transgender behavior, especially in the performance arts. Despite the presence of LGBTQ individuals in diverse cultures, European and Christian colonizers rejected behaviors that deviated from their views of masculine and feminine roles and enforced sodomy laws, which defined certain sexual acts as crimes. Consequently, through much of history, LGBTQ individuals were stigmatized, arrested and labeled deviant.

Although there had been organizations that advocated for the acceptance of same sex relationships since the late 19th century, the uprising at the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village on June 28, 1969 was an important turning point (Morris, 2016). Fed up with ongoing police raids, patrons of the bar fought back and galvanized the gay liberation movement. The 1970s saw the creation of political organizations focused on gay rights. Lesbian movements also emerged as many females felt excluded from the leadership of most gay liberation groups. Another important turning point was in 1973 when the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. No longer would the LGBTQ community be at risk for a psychiatric diagnosis, job dismissal, or loss of a child custody case.

New legal gains for gay and lesbian couples in America occurred in 2000 when same-sex civil unions were recognized in Vermont. By 2004, same-sex marriages took place in Massachusetts and on June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees same-sex marriage. The 21st century has also seen the emergence of greater transgender visibility and support for transgender equal rights, as well as the increased use of non-binary terms (Morris, 2016). On June 15, 2020, the United States Supreme Court ruled that gay, lesbian, and transgender people are protected from employment discrimination. A majority of the court justices determined that the Civil Rights Act of 1964, barring discrimination based on sex, included discrimination against people based on their sexual orientation or gender identity (Sherman, 2020).

Despite these gains and visibility, there is still a perception held by many that a transwoman is not really a woman. For example, author J. K. Rowling was criticized for emphasizing the definition of a woman based on menstruation. In fact, some feminists do not include transwomen as women and align with gender-critical feminism, which advocates reserving women’s spaces for ciswomen (Zanghellini, 2020). A reason given for the exclusion of transwomen as women, is that transwomen were socialized as cismales and not as women. Therefore, transwomen lack the distinctive experience of sex-based subordination faced by ciswomen. Additionally, gender-critical feminism asserts that transwomen would undermine the safety of ciswomen by accessing women-only spaces (e.g., bathrooms and changing rooms), and thus women’s bodies. Consequently, ciswomen would be vulnerable to enduring predatory male behavior. Further discussions of individuals in the LGBTQ community occur in later modules.

Transgender Rights and Legal Challenges

Twenty-six U.S. states have recently adopted policies to halt or severely restrict access to gender-affirming care, potentially affecting 39% of transgender youth (ages 13-17) who live in these states (Dawson & Kates, 2024). Supporters of these laws argue that there is insufficient evidence regarding the effectiveness of gender-affirming care and that teenagers are too immature to make life-changing decisions (Weimer, 2024). However, many medical organizations, including the American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association, and the American Psychiatric Association, have rejected these laws, emphasizing the importance of these treatments for transgender youth (Advocates for Trans Equality, 2024). Many of these state laws are now being challenged in the Supreme Court.

In addition to restrictions on gender-affirming care, concerns have arisen over transgender women competing in women’s sports. In a recent Arizona case (Doe v. Horne), a 9th Circuit federal judge ruled in favor of two transgender female athletes who wished to compete in girls’ sports at school. Both athletes had been on puberty blockers since the age of 11, before the onset of puberty. The judge sided with a lower court ruling, stating that there is little difference in the physical abilities of boys and girls prior to puberty (Walsh, 2024). However, the growing restrictions on gender-affirming care may present challenges for transgender youth attempting to participate in athletics.

The Biden administration’s attempt to protect transgender athletes under Title IX was struck down by a federal judge in early 2025, adding further uncertainty for colleges striving to meet the regulations of Title IX (Knott & Alonso, 2025). The changes to Title IX would have granted transgender students the right to use bathrooms and locker rooms, as well as dress and groom themselves in accordance with their gender identity, among other protections for LGBTQ+ students and women reporting sex-based harassment, and pregnant and parenting students (National Women’s Law Center, 2024).

Main Themes of Gender Studies

There are a few themes that run throughout the text. The first theme, essentialism versus constructivism, centers on how we perceive the true nature of gender. This central belief strongly impacts how we interpret and react to the concept of gender, gender issues, and the people who occupy various gender categories. The second theme focuses on the dynamics of power in a society and how certain forms of power often reside with one gender more than the other. One dynamic of power is demonstrated through sexism. This shapes the experiences, opportunities, and developmental course for people. The final theme is intersectionality. Gender is but one of a myriad of other social categories (e.g., age, race, ability, wealth) that influence people’s lives. These themes underlie many of the topics and issues discussed in the rest of the text.

Essentialism vs. Constructivism:

Identities are the categories we use to define both ourselves and other people. In many societies the boundaries between different categories of people seem clear and straightforward. Someone is a male, Hispanic, heterosexual, and Catholic. This “black and white” way of thinking about the world is at the heart of essentialism. In essentialism the characteristics that are a part of a category are assumed to be universal, inherent, and unambiguous (Newman, 2017). These characteristics are viewed as part of the individual, not embedded within a social context. The categories in which we place ourselves and others are also assumed to be immutable. For example, the essentialist view assumes that people cannot change their sexual orientation. If someone later in life enters into a same-sex relationship, from the essentialist view, this person has always been homosexual. Sex, gender, and sexual orientation are viewed as unchanging characteristics of the individual.

This essentialist view can have important consequences. If one believes that an inherent characteristic of a man is to be dominant and assertive, then should they not, by the very virtue of being men, hold the positions of power? If it is an essential quality of women to nurture, should they not be given the role of caregiver? From this perspective it is only “natural” that women take care of others and that men lead. This can lead to, and be used to, justify social inequalities between groups in a society.

In contrast, constructivism, also called social constructivism, argues that society creates what we believe to be true (Newman, 2017). Thus, what we believe to be reality is always a creation of our culture and time period. Geocentricity, the belief that the sun and other planets revolved round the earth, was a commonly held view until it was eventually displaced by the work of Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler. Just like our knowledge of the universe has changed over time, so too has our understanding of sex and gender. The constructivist view recognizes that such identifiers depend on the context. The meaning of such categories are different between cultures and can change over time. For instance, the original definition of heterosexual was someone who preferred both sexes (Katz, 2003). This means these categories are historically or culturally specific and, contrary to the essentialist view, are often fluid rather than fixed. This book will take the constructionist view about sex and gender, and you will see that “gendered behavior results from a complex interplay of genes, gonadal hormones, socialization, and cognitive development related to gender identification” (Hines, 2011, p. 70).

Dynamics of Power:

Human societies throughout the ages have typically been based on hierarchies with dominant groups holding power over subordinate groups. Power can come in many forms in a society. Structural power determines who makes the decisions and laws that govern the society and can also determine who holds, and metes out, resources. Structural power controls society at large and this is typically in the hands of men. Dyadic power refers to the power to initiate intimate relationships and control the decisions in those relationships. Dyadic power controls more the family and home. In many, but not all cultures and families, women control more of the dyadic power (Wingood & DiClemente, 2000).

Patriarchy is the term used to describe societies that place power and resources in the hands of males. Most patriarchal societies are also patrilineal, meaning that lineage and wealth in a family is passed down from fathers. Patrilocal describes cultures where women leave their families to live with or near their husband’s family. Matriarchy is the term used to describe societies that place structural power and resources in the hands of females. There is little evidence that true matriarchal societies occurred in human history (Bosson et al., 2019). However, there is evidence of matrilineal societies, even today, where the lineage and wealth is passed down from mothers, and matrilocal cultures where men move to live with or near their wife’s family.

Sexism:

The dynamics of power in a culture influences the experiences of different genders. This is illustrated in the concept of sexism. Sexism or gender discrimination is a form of prejudice and/or discrimination based on a person’s sex or gender (Bosson, et al., 2019). Sexism can affect any sex that is marginalized or oppressed in a society; however, it is particularly documented as affecting females. It has been linked to stereotypes and gender roles and includes the belief that males are intrinsically superior to other sexes and genders. Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape, and other forms of sexual violence.

The dynamics of power in a culture influences the experiences of different genders. This is illustrated in the concept of sexism. Sexism or gender discrimination is a form of prejudice and/or discrimination based on a person’s sex or gender (Bosson, et al., 2019). Sexism can affect any sex that is marginalized or oppressed in a society; however, it is particularly documented as affecting females. It has been linked to stereotypes and gender roles and includes the belief that males are intrinsically superior to other sexes and genders. Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape, and other forms of sexual violence.

Sexism can exist on a societal level, such as in hiring, employment opportunities, and education. In the United States, women are less likely to be hired or promoted in male-dominated professions, such as engineering, aviation, and construction (Funk & Parker, 2018). In many areas of the world, young girls are not given the same access to nutrition, healthcare, and education as boys. Sexism also includes people’s expectations of how members of a gender group should behave. For example, women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing; when a woman behaves in an unfriendly or assertive manner, she may be disliked or perceived as aggressive because she has violated a gender role (Rudman, 1998). In contrast, a man behaving in a similarly unfriendly or assertive way might be perceived as strong or even gain respect in some circumstances.

Glick and Fiske (1997) proposed the theory of ambivalent sexism, which explains how sexism can simultaneously take the form of both hostility and benevolence. Ambivalent sexism includes both benevolent sexism, that is, positive attitudes toward an individual in a gender group often when they engage in traditional roles and hostile sexism; that is, negative attitudes toward an individual in a gender group often when they engage in non-traditional roles. For example, King (2015) investigated how store employees view pregnant women when applying for a job and when asking for help. In field experiments, women wearing a pregnancy prosthesis encountered more subtle forms of discrimination, including rudeness, hostility, and decreased eye contact, when applying for a retail job than when they did not appear pregnant. Conversely, when the same women asked for help finding a gift, she received more positive reactions and greater assistance when appearing to be pregnant. Ambivalent sexism explains these results by focusing on how the women demonstrated traditional gender roles. The women were “punished” when asking for a job (hostile sexism) and “rewarded” when asking for assistance (benevolent sexism). Both types of sexism support patriarchy and maintain traditional gender roles for both women and men.

Intersectionality:

In 1976, five Black women from Missouri filed a law suit alleging that General Motors discriminated against Black women. In DeGraffenreid v. General Motors, these women argued they were excluded from employment due to compound discrimination. They contended that only white women were hired for office and secretarial jobs. The courts weighed the allegations of race and gender discrimination separately and found that the employment of Black male factory workers disproved racial discrimination, and the employment of White female office workers disproved gender discrimination. The court declined to consider compound discrimination and dismissed the case. Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw often refers to this case as an inspiration for developing intersectional theory, or the study of how overlapping or intersecting social identities relate to oppression, domination or discrimination.

According to Crenshaw (1991), the concept of intersectionality, arising from intersectional theory, identifies a mode of analysis integral to gender and sexuality studies. Notions of gender, and the way a person’s gender is interpreted by others, are always impacted by the way that person’s race is interpreted. For example, a person is never received as just a woman, but how that person is racialized impacts how the person is received as a woman. So, notions of blackness, brownness, and whiteness always influence gendered experience, and there is no experience of gender that is outside of an experience of race. In addition to race, gendered experience is also shaped by age, sexuality, class, and ability; likewise, the experience of race is impacted by gender, age, class, sexuality, and ability (Kang et al., 2017).

Older, minority women can face ageism, racism, and sexism, often referred to as triple jeopardy (Hinze, et al., 2012), which can adversely affect their life in late adulthood. Older adults who are African American, Mexican American, and Asian American experience psychological problems that are often associated with discrimination by the White majority (Youdin, 2016).

When socioeconomic status is added into the mix, the experiences of older men and women can greatly differ. According to Quinn and Cahill (2016), the poverty rate for older adults varies based on gender, marital status, race, and age. Women aged 65 or older were 70% more likely to be poor than men, and older women aged 80 and above have higher levels of poverty than those younger. Married couples are less likely to be poor than nonmarried men and women, and poverty is more prevalent among older racial minorities. In 2017 the poverty rates for White older men (5.8%) and White older women (8.0%) were lower than for Black older men (16.1%), Black older women (21.5%), Hispanic older men (14.8%), and Hispanic older women (19.8%) (Li & Dalaker, 2019).

Understanding intersectionality requires a particular way of thinking. It is different than how many people imagine identities operate. An intersectional analysis of identity is distinct from single-determinant identity models and additive models of identity. A single determinant model of identity presumes that one aspect of identity, say, gender, dictates one’s access to or disenfranchisement from power. An example of this idea is the concept of “global sisterhood or brotherhood,” or the idea that all women or all men across the globe share some basic common political interests, concerns, and needs (Morgan 1996). Unfortunately, if the analysis of social problems stops at gender, what is missed is an attention to how various cultural contexts shaped by race, religion, and access to resources may actually place some men’s and women’s needs at cross-purposes to other men’s and women’s needs. Therefore, this approach obscures the fact that men and women in different social and geographic locations face different problems. Although many white, middle-class women activists of the mid-20th century US fought for freedom to work and legal parity with men, this was not the major problem for women of color or working-class white women who had already been actively participating in the US labor market as domestic workers, factory workers, and enslaved laborers since early US colonial settlement. Campaigns for women’s equal legal rights and access to the labor market at the international level are shaped by the experience and concerns of white American women, while women of the global south (a term used to replace third world nations), in particular, may have more pressing concerns: access to clean water, access to adequate health care, and safety from the physical and psychological harms of living in tyrannical, war-torn, or economically impoverished nations.

In contrast to the single-determinant identity model, the additive model of identity simply adds together privileged and disadvantaged identities for a slightly more complex picture. For instance, a Black man may experience some advantages based on his gender, but has less access to power based on his race. The additive model does not take into account how our shared cultural ideas of gender are racialized and our ideas of race are gendered and that these ideas influence access to resources and power, such as material, political, and interpersonal. We cannot simply pull these identities apart because they are interconnected and mutually enforcing. In summary, an intersectional perspective examines how identities are related to each other in our own experiences and how the social structures of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability intersect for everyone. As opposed to single-determinant and additive models of identity, an intersectional approach develops a more sophisticated understanding of the world and how individuals in differently situated social groups experience differential access to both material and symbolic resources.

The following chapters will discuss the contemporary theories and research on gender.